China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

"Around the World of a Bicycle - Cycling through China in 1886 "

Part 6

Cycling through China - Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part7 | Part 8 | Around the World on a Bicycle - Maps and Pictures

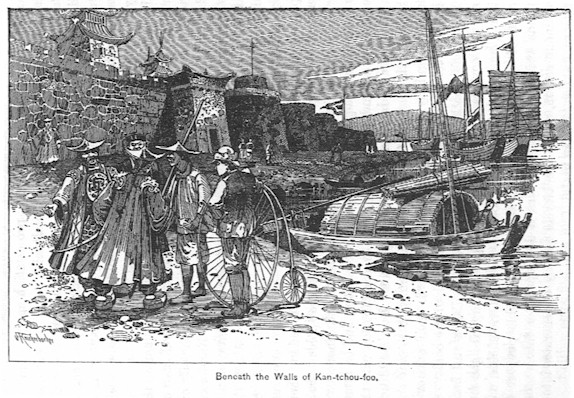

The barometer of satisfaction at the prospect of reaching Kui-kiang before the appearance of old age rises from zero-level to a quite flattering height, as I find the pathways more than half ridable after delivering myself of the dead weight of native "assistance." Twelve miles farther and I am approaching the grim high walls of a large city that instinctively impresses me as being Kan-tchou-foo. The confused babel of noises within the teeming wall-encompassed city reaches my ears in the form of an "ominous buzz," highly suggestive of a hive of bees, into the interior of which it would be extremely ticklish workfor a Fankwae to enter. "Half an hour hence," I mentally speculate, "the pitying angels may be weeping over the spectacle of my seal-brown roasted remains being dragged about the streets by the ribald and exultant rag, tag, and bobtail of Kan-tchou-foo."

Reflecting on the horrors of cotton, peanut-oil, and fire, I sit down for half an hour at a peanut-seller's stall, eat peanuts, and meditatively argue the situation of whether it would be better, if seized by a murderous mob, to take the desperate chances of being, like Cameron, rescued at the last minute from the horrors of incineration, or to take my own life. Fourteen cartridges and a 38 Smith & Wesson is the sum total of my armament. Emptying my revolver among the mob, and then being caught while reloading, would mean a lingering death by the most diabolical tortures, processes that the heathen Chinee has reduced to a refinement of cruelty unsurpassed in the old Spanish inquisition chambers.

The saucer of peanuts eaten, I pursue my way along the cobblestone path leading to the gate, without having come to any more definite conclusion than to keep cool and govern my actions according to circumstances. Ten minutes after taking this precaution I am trundling along a paved street, somewhat wider than the average Chinese city street, in the thick of the inevitable excited crowd.

The city probably contains two hundred thousand people, judging from the length of this street and the wonderful quantity and richness of the goods displayed in the shops. Along this street I see a more lavish display of rich silks, furs, tiger-skins, and other evidences of opulence than was shown me at Canton. The pressure of the crowds reduces me at once to the necessity of drifting helplessly along, whithersoever the seething human tide may lead. Sometimes I fancy the few officiously interested persons about me, whom I endeavor to question in regard to the hoped-for Jesuit mission, have interpreted my queries aright and are piloting me thither; only to conclude by their actions, the next minute, that they have not the remotest conception of my wants, beyond reaching the other side of the city. Now and then some ruffian in the crowd, in a spirit of wanton devilment, utters a wild, exultant whoop and raises the cry of "Fankwae. Fankwae." The cry is taken up by others of his kind, and the whoops and shouts of "Fankwae" swell into a tumultuous howl.

Anxious moments these; the spirit of wanton mischief fairly bristles through the crowd, evidently needing but the merest friction to set it ablaze and render my situation desperate. My coat-tail is jerked, the bicycle stopped, my helmet knocked off, and other trifling indignities offered; but to these acts I take no exceptions, merely placing my helmet on again when it is knocked off, and maintaining a calm serenity of face and demeanor.

A dozen times during this trying trundle of a mile along the chief business thoroughfare of Kan-tchou-foo, the swelling whoops and yells of "Fankwae" seem to portend the immediate bursting of the anticipated storm, and a dozen times I breathe easier at the subsidence of its volume. The while I am still hoping faintly for a repetition in part of my delightful surprise at Chao-choo-foo, we arrive at a gate leading out on to a broad paved quay of the Kan-kiang, which flows close by the walls.

Here I first realize the presence of Imperial troops, and awaken to the probability that I am indebted to their known proximity for the self- restraint of the mob, and their comparatively mild behavior. These Celestial warriors would make excellent characters on the spectacular stage; their uniforms are such marvels of color and pattern that it is difficult to disassociate them from things theatrical. Some are uniformed in sky blue, and others in the gayest of scarlet gowns, blue aprons with little green pockets, and blue turbans or Tartar hats with red tassels. Their gowns and aprons are patterned so as to spread out to a ridiculous width at bottom, imparting to the gay warrior an appearance not unlike an opened fan, his head constituting the handle.

As a matter of fact, the soldiers of the Imperial army are the biggest dandies in the country; when on the march coolies are provided to carry their muskets and accoutrements. As seen today, beneath the walls of Kan-tchou-foo, they impress me far more favorably as dandies than as soldiers equal to the demand of modern warfare.

Like soldiers the whole world round, however, they seem to be a good-natured, superior class of men; no sooner does my presence become known than several of them interest themselves in checking the aggressive crowding of the people about me. Some of them even accompany me down to the ferry and order the ancient ferryman to take me across for nothing. This worthy individual, however, enters such a wordy protestation against this that I hand him a whole handful of the picayunish tsin. The soldiers make him give me back the over-payment, to the last tsin. The sordid money-making methods of the commercial world seem to be regarded with more or less contempt by the gallant sons of Mars everywhere, not excepting even the soldiers of the Chinese army.

The scene presented by the city and the camp from across the river is of a most pronounced mediaeval character, as well as one of the prettiest sights imaginable. The grim walla of the city extend for nearly a mile along the undulating bank of the Kan-kiang, with a narrow strip of greensward between the solid gray battlements and the blue, wind-rippled waters of the river. Along the whole distance, rising and falling with the undulations of the bank, are ranged a continuous row of gayly fluttering banners-red, purple, blue, green, yellow, and all these colors combined in others that are striped as prettily as the prettiest of barber-poles-probably not less than five hundred flags. These multitudinous banners flutter from long, spear-headed bamboo-staves, and of themselves present a wonderfully pretty effect in combination with the blue waters, the verdant bank, and the gray walls. But in addition to these are thousands of soldiers, equally gaudy as to raiment, reclining irregularly along the same greensward, each warrior a bright bit of coloring on the verdant groundwork of the bank.

Over variable paths and through numerous villages and hamlets my way now leads, my next objective point being Ki-ngan-foo. At first a country of curious red buttes, terraced rice-fields, and reservoirs of mountain-drift water, serving the double purpose of fish-ponds and irrigating reservoirs, it develops later into a more mountainous region, where the bicycle quickly degenerates into a thing more ornamental than useful.

On a narrow mountain-trail is met a gentleman astride of a chunky twelve- hand pony. This diminutive steed is almost concealed beneath a wealth of gay trappings, to which are attached hundreds of jingling bells that fill the air with music as he walks or jogs along. In his fright at the bicycle, or me, he charges wildly up the steep mountain-slope, unseating his rider and making for the mountain-top like the all-possessed. His rider takes the sensible course of immediately pursuing the pony, instead of wasting time in unprofitable fault-finding with me.

Few people of these obscure mountain-hamlets have ever seen a Fankwae; many, doubtless, have never even heard of the existence of such queer beings. They gather in a crowd about me when I stay to seek refreshments; the general query of "What is he? what is he?" passed from one to another, sometimes elicits the laconically expressed information of" Fankwae" from some knowing villager or traveller passing through, but often their question remains unanswered, because among the whole assembly there is nobody who really knows what I am.

The wonderful industry of these people is more apparent in this mountain- country than anywhere else. The valleys are very narrow, often little more than mere ravines between the mountains, and wherever a square yard of productive soil is to be found it is cultivated to its utmost capacity. In places the mountain-ravines are terraced, to their very topmost limits, tier after tier of substantial rock wall banking up a few square yards of soil that have been gathered with infinite labor and patience from the ledges and crevices of the rocky hills. The uppermost terrace is usually a pond of water, gathered by the artificial drainage of still higher levels, and reserved for the irrigation of the score or more descending "steps" of the rice-growing stairway beneath it.

Notwithstanding the mountainous nature of the country and the dallying progress through Kan-tchou-foo, so lightsome does it seem to be once more journeying along, free and unencumbered, that I judge my day's progress to be not less than fifty miles when nightfall overtakes me in a little mountain-village. It is the first day's progress in China with which I have been really satisfied. Nevertheless, it has been a toilsome day, taken altogether, and when nothing but tea and rice confronts me at supper the reward seems so wretchedly inadequate that I rise in rebellion at once.

Neither eggs, fish, nor meat are to be obtained, the good woman at the little hittim explains in a high key; neither loan, ue, nor ue-ah, nothing but ch'ung-ch'a and mai. The woman is evidently a dear, considerate mortal, however, for she surveys my evident disgust with sorrowful visage, and then, suddenly brightening up, motions for me to be seated and leaves the house. Presently the good dame returns with a smile of triumph on her face and an object in her hand that, from casual observation, might be the hind-quarters of a rabbit. Bringing it to me in the most matter- of manner, she holds it near my face and, pointing to it with the air of a cateress proudly conscious of having secured something that she knows will be unusually acceptable to her guest, she explains "me-aow, me-aow!" The woman's naivete is simply sublime, and her sagacity in explaining the nature of the meat by imitating a kitten's cry instead of telling me its Chinese name stamps her as superior to her surroundings; but, for all that, I conclude to draw the line at kitten and sup off plain rice and tea. "Me-aow, me-aow" might not be altogether objectionable if one knew it to have been a nice healthy kitten, but my observations of Chinese unsqueamishness about the food they eat leaves an abundance of room for doubt about the nature of its death and its suitableness for human consumption. I therefore resist the temptation to indulge.

A clear morning and a white frost usher in the commencement of another march across the mountains, over cobbled paths for the greater part of the forenoon. The sun is warm, but the mountain-breezes are cool and refreshing. About noon I ferry across a large tributary of the Kan-kiang, and follow for miles a cobble-stone path that leads down its eastern bank.

According to my map, Ki-ngan-foo should be about fifty miles south of Kan-tchou-foo, so that I ought to have reached there by noon to-day. All due allowance, however, must be made for the map-makers in mapping out a country where their opportunities for accuracy must have been of the meagerest kind. Small occasion for fault-finding under the circumstances, I think, for in the middle of the afternoon the gray battlements, the pagodas, and the bright coloring of military flags a few miles farther down stream tell me that the geographers have not erred to any considerable extent.

It is about sunset when I enter the gates and find myself within the Manchu quarter, that portion of the city walled off for the residence of the Manchu garrison and their families. The hittim to which the quickly gathering crowd conduct me is found to be occupied by a rather prepossessing female, who, however, looks frightened at my approach and shuts the door. Nor will she consent to open it again until reassured of my peaceful character by the lengthy explanation of the people outside, and a searching scrutiny of my person through a crack. After opening the door again, and receiving what I opine to be a statement of the financial possibilities of the situation from some person who has heard fabulous accounts of the Fankwaes' liberality, her apprehensiveness dissolves into a smile of welcome and she motions for me to come in.

The evening is chilly, and everybody is swollen out to ridiculous proportions by the numerous thick-quilted garments they are wearing. All present, whether male or female, are likewise distinguished by abnormally protruding stomachs. Being Manchus, and therefore the accredited warriors of the country, it occurs to ine that perhaps the fashionable fad among them is to pad out their stomachs in token of the possession of extraordinary courage, the stomach being regarded by the Chinese as the seat of both courage and intelligence. In the absence of large stomachs provided by nature, perhaps these proud Manchus come to the correction of niggardly nature with wadding, as do various hollow-chested people in the "regions of mist and snow," the dreary, sunless land whence cometh the genus Fankwae.

But are the females also ambitious to be regarded as warriors, Amazonian soldiers, full of courage and warlike aspirations. As though in direct reply to my mental queries, a woman standing by solves the problem for me at once by producing from beneath her garments a wicker-basket containing a jar of hot ashes; stirring the deadened coals up a little she replaces it, evidently attaching it to her garments underneath by a little hook.

Among the hundreds of visitors that drop in to see the Fankwae and his bicycle is an intelligent old officer who actually knows that the great country of the Fankwaes is divided into different nationalities; either that, or else he thinks the Fankwaes have another name, said name being "Ying-yun" (English). Some idea of the dense ignorance of the Chinese of the interior concerning the rest of the world may be gathered from the fact that this officer is the first person since leaving Chao-choo-foo, upon whom the word "Ying-yun" has not been wholly thrown away.

Scenes of more than democratic equality and fraternity are witnessed in this Manchu hittim, where silk-robed mandarins and uncouth ragamuffins stand side by side and enjoy the luxury of seeing me take lessons in the use of the chop-sticks. All through China one cannot fail to be impressed with the freedom of inter- course between people of high and low degree; beggars with unwashed faces and disgusting sores and wellnigh naked bodies stand and discuss my appearance and movements with mandarins of high degree, without the least show of presumption on the one hand or condescension on the other.

Fully under the impression that Ki-ngan-foo has now peacefully come and peacefully gone from the pale of my experiences, I follow along awful stone paths next morning, leading across a level, cultivated country for several miles. Before long, however, a country of red clay hills and limited cultivable depressions is reached, where well-worn foot-trails over the natural soil afford more or less excellent going. In this particular district the women are observed to be all golden lilies, whereas the proportion of deformed feet in other rural districts has been rather small. Seeing that deformed feet add fifty or a hundred per cent, to the social and matrimonial value of a Chinese female, one cannot help applauding the enterprise of the people in this district as compared to the apathy existing on the same subject in some others. The comparative poverty of their clayey undulations has doubtless awakened them to the opportunities of increasing values in other directions. Hence they convert all their female infants into golden lilies, for whom some prospective husband will be willing to pay a hundred dollars more than if they were possessed of vulgar extremities as provided by nature.

The people hereabout seem unusually timid and alarmed at my strange appearance; it is both laughable and painful to see the women hobble off across the fields, frightened almost out of their wits. At times I can look about me and, within a radius of five hundred yards, see twenty or thirty females, all with deformed feet, scuttling off toward the villages with painful efforts at speed. One might well imagine them to be a colony of crippled rabbits, alarmed at the approach of a dog, endeavoring to hobble away from his destructive presence.

In the villages they seem equally apprehensive of danger, making it somewhat difficult to obtain anything to eat. At one village where I halt for refreshments the people scurry hastily into their houses at seeing me coming, and peep timidly out again after I have passed. Leaning the bicycle against a wall, I proceed in search of something to eat. A basket of oranges first attracts my attention; they are setting just inside the door of a little shop. The two women in charge look scared nearly out of their wits as I appear at the door and point to the basket; both of them retreat pell-mell into a rear apartment, and, holding the door ajar, peep curiously through to see what I am going to do. While my attention is directed for a moment to something down the street, one daring soul darts out and bears the basket of oranges triumphantly into the back room. For this heroic deed I beg to recommend this brave woman for the Victoria Cross; among the golden lilies of the Celestial Empire are no doubt many such brave souls, coequal with Grace Darling or the Maid of Saragossa.

Baffled and out-generaled by this brilliant sortie, I meander down to the other end of the v^lage and invade the premises of an old man engaged in chopping up a piece of pork with a cleaver. The gallant pork-butcher gathers up the choicest parts of his meat and carries them into a rear room; with a wary yet determined look in his eye he then returns, and proceeds to mince up the few remaining odds and ends. It is plainly evident that he fancies himself in dangerous company, and is prepared to defend himself desperately with his meat-chopper in case he gets cornered up.

Finally I discover a really courageous individual, in the person of a man presiding over a peanut and treacle-cake establishment; this man, while evidently uneasy in his mind, manfully steels his nerves to the task of attending to my wants. Presently the people begin to gather at a respectful distance to watch me eat, and five minutes later, by a judicious distribution of a few saucers of peanuts among the youngsters, I gain their entire confidence.

About four o'clock in the afternoon my road once again brings me to a ferry across the Kan-kiang. Just previous to reaching the river, I meet on the road eight men, carrying a sedan containing a hideous black idol about twice as large as a man. A mile back from the ferry is another large walled city with a magnificent pagoda; this city I fondly imagine to be Lin-kiang, next on my map and itinerary to Ki-ngan-foo, and I mentally congratulate myself on the excellent time I have been making for the last two days.

Across the ferry are several official sampans with a number of boys gayly dressed in red and carrying old battle-axes; also a small squad of soldiers with bows and arrows. No sooner does the ferryman land me than the officer in charge of the party, with a wave of his hand in my direction, orders a couple of soldiers to conduct me into the city; his order is given in an off-hand manner peculiarly Chinese, as though I were a mere unimportant cipher in the matter, whose wishes it really was not worth while to consult. The soldiers conduct me to the city and into the yamen or official quarter, where I am greeted with extreme courtesy by a pleasant little officer in cloth top-boots and a pigtail that touches his heels. He is one of the nicest little fellows I have met in China, all smiles and bustling politeness and condescension; a trifle too much of the latter, perhaps, were we at all on an equality; but quite excusable under the conditions of Celestial refinement and civilization on one side, and untutored barbarism on the other.

Having duly copied my passport (apropos of the Chinese doing almost everything in a precisely opposite way to ourselves may be pointed out the fact that, instead of attaching vises to the traveller's passport, like European nations, each official copies off the entire document), the little officer with much bowing and scraping leads the way back to the ferry. My explanation that I am bound in the other direction elicits sundry additional bobbings of the head and soothing utterances and smiles, but he points reassuringly to the ferry. Arriving at the river, the little officer is dumbfounded to discover that I have no sampan-that I am not travelling by boat, but overland on the bicycle. Such a possibility had never entered his head; nor is it wonderful that it should not, considering the likelihood that nobody, in all his experience, had ever travelled to Kui-kiang from here except by boat. Least of all would he imagine that a stray Fankwae should be travelling otherwise.

At the ferry we meet the officer who first ordered the soldiers to take me in charge, and who now accompanies us back to the yamen. Evidently desirous of unfathoming the mystery of my incomprehensible mode of travelling through the country, these two officers spend much of the evening with me in the hittim smoking and keeping up an animated effort to converse. Notwithstanding my viceregal passport, the superior officer very plainly entertains suspicions as to my motives in undertaking this journey; his superficial politeness no more conceals his suspicions than a glass globe conceals a fish. Before they take their departure three yameni-runners are stationed in my room to assume the responsibility for my safe-keeping during the night.

An hour or so is spent waiting in the yamen next morning, apparently for the gratification of visitors continually arriving. When the yamen is crowded with people I am provided with a boiled fish and a pair of chop- sticks. Witnessing the consumption of this fish by the Fankwae is the finale of the "exhibition," and candor compels me to chronicle the fact that it fairly brings down the house.

Next: Cycling through China - Part 7

Cycling through China - Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part7 | Part 8 | Around the World on a Bicycle - Maps and Pictures

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.