China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

"Around the World of a Bicycle - Cycling through China in 1886 "

Part 5

Cycling through China - Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part7 | Part 8 | Around the World on a Bicycle - Maps and Pictures

CHAPTER XVIII.

DOWN THE KAN-KIANG VALLEY.

The country is still nothing but river and mountains, and a sampan is engaged to float me down the Kan-kiang as far as Kan-tchou-foo, from whence I hope to be able to resume my journey a-wheel. The water is very low in the upper reaches of the river, and the sampan has to be abandoned a few miles from where it started. I then get two of the boatmen to carry the wheel, intending to employ them as far as Kan-tchou-foo.

From the stories current at Canton, the reputation of Kan-tchou-foo is rather calculated to inspire a lone Fankwae with sundry misgivings. Some time ago an English traveller, named Cameron, had in that city an unpleasantly narrow escape from being burned alive. The Celestials conceived the diabolical notion of wrapping him in cotton, saturating him with peanut-oil, and setting him on fire. The authorities rescued him not a moment too soon.

Ere traversing many miles of mountain-paths we emerge upon a partially cultivated country, where the travelling is somewhat better than in Quang-tung. The Mae-ling Pass was the boundary line between the provinces of Quang-tung and Kiang-se; my journey from Nam-ngan will lead me through the whole length of the latter great province, between three hundred and four hundred miles north and south.

The paths hereabout are of dirt mostly, and although wretched roads for a wheelman in the abstract, are nevertheless admirable in comparison with the stone-ways of Quang-tung. Gratified at the prospect of being able to proceed to Kui-kiang by land after all, I determine at once that, if the country gets no worse by to-morrow, I will dismiss the boatmen and pursue my way alone again on the bicycle. This resolve very quickly develops into an earnest determination to rid myself of the incubus of the snail-like movements of my new carriers, who are decidedly out of their element when walking, as I am very quickly brought to understand by the annoying frequency of their halts at way-side tea-houses to rest and smoke and eat.

Ere we are five miles from the sampan these festive mariners of the Kan- kiang have developed into shuffling, shirking gormandizers, who peer longingly into every eating-house we pass by and evince a decided tendency to convert their task into a picnic. Finding me uncomplaining in footing their respective "bills of lading" at the frequent places where they rest and indulge their appetites for tid-bits, they advance, in the brief space of four hours, from a simple diet of peanuts and bubbles of greasy pastry to such epicurean dishes as pickled duck, salted eggs, and fricasseed kitten!

Fricasseed kitten is all very well for people who have been reared in the lap of luxury, and tenderly nurtured; but neither of these half-clad Kan-kiang navigators was born with the traditional silver spoon. From infancy they have had to thrive the best way they could on rice, turnip- tops, peanuts, and delusive expectations of pork and fish; their assumption of the delicacies above mentioned betrays the possession of bumps of assurance bigger than goose-eggs. It is equivalent to a moneyless New York guttersnipe sailing airily into Delmonico's and ordering porter-house steak and terrapin, because some benevolent person volunteered to feed him for a day or two at his expense. Fearful lest their ambitious palates should soar into the extravagant and bankrupting realms of bird-nest soup, shark's fins, and deer-horn jelly, I firmly resolve to dispense with their services at the first favorable opportunity.

Many of the larger villages we pass through are walled with enormously massive brick walls, all bearing evidence of battering at the hands of the Tai-pings. Owing to the frequent restings of the carriers we are overtaken toward evening by a fellow boat-passenger, Oolong, who after our departure determined to follow our enterprising example and walk to Kan-tchou-foo. He comes trudging briskly along with a little white tea-pot swinging in his hand and an umbrella under his arm.

The day is disagreeably cold by reason of the chilly typhoons that blow steadily from the north. I have considerately encased the thinnest clad carrier in my gossamer rubbers to shield him from the wind, but Oolong is even thinner clad than he, and he has to hustle along briskly to keep his Celestial blood in circulation.

No sooner do we reach the hittim where it is proposed to remain over night than poor Oolong gets into trouble by appropriating to his own use the quilted garment of one of the employes of the place, which he finds lying around loose. The irate owner of the garment loudly accuses Oolong of wanting to steal it, and notwithstanding his vigorous protestations to the contrary he is denounced as a thief and summarily ejected from the premises.

The last I ever see of Oolong and his white tea-pot and umbrella is when he pauses for a moment to give his accusers a bit of his mind before vanishing into outer darkness.

The morning is quite wintry, and the people are clad in the seasonable costumes of the country. Huge quilted garments are put on one over another until their figures are almost of ball-like rotundity; the hands are drawn up entirely out of sight in the long, loosely flowing sleeves, while the head is half-hidden by being drawn, turtle-like, into their blue-quilted shells. Like the Persians, they seem nipped and miserable in the cold; looking at them, standing about with humped backs and pinched faces this morning, I wonder, with the Chinaman's happy nonchalance about committing suicide, why they don't all seek relief within the nice warm tombs at the end of the village. Surely it can be nothing but their rampant curiosity, urging them to live on and on in the hopes of seeing something new and novel, that keeps them from collapsing entirely in the winter.

My epicurean carriers indulge largely in chopped cayenne peppers this morning, which they mis liberally with their food.

The paths at least get no worse than they were yesterday, and to-day I meet the first passenger-wheelbarrow, with its big wheel in the centre, a bulky female with a baby on one side, and a bale of merchandise on the other. Sometimes our road brings us to the banks of the Kan-kiang, and most of the time, even when a mile or two away, we can see the queer, corrugated sails of the sampans.

Once to-day we happen upon a fleet of fourteen cormorant fishers at a moment when the excitement of their pursuit is at its height. About seventy or eighty cormorants are diving and chasing about among a shoal of fish in a big silent pool, while fourteen wildly excited Chinamen, clad in abbreviated breech-cloths, dart their bamboo rafts about hither and thither, urging each one his own cormorants to dive by tapping them smartly with their poles. The scene is animated in the extreme, a unique picture of Chinese river-life not to be easily forgotten.

About two o'clock in the afternoon we arrive at a city that I flatter myself is Kan-tchou-foo; all attempts to question the carriers or anybody else in regard to the matter results in the hopeless bewilderment of both them and myself. The carriers are not such ignoramuses in the art of pantomime, however, but that they are able to announce their intention of stopping here for the remainder of the day, and night.

The liberality of my purse for a short day and a half, with its concomitant luxurious living, has so thoroughly demoralized the unaccustomed river-men, that they encroach still further upon my bounty and forbearance by revelling all night in the sensuous delights of opium, at my expense, and turning up in the morning in anything but fit condition for the road. Putting this and that together, I conclude that we have not yet readied Kan-tchou-foo; but the carriers have developed into an insufferable nuisance, a hinderance to progress, rather than a help, so I determine to take them no farther.

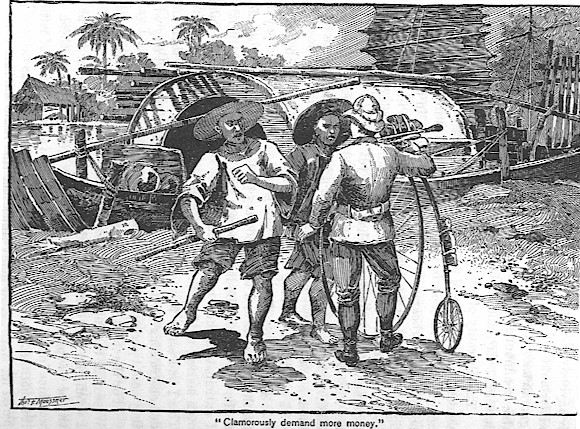

I tell them nothing of my intentions until we reach a lonely spot a mile from the city. Here I tender them suitable payment for their services and the customary present, attach my loose effects to the bicycle and about my person, and motion them to return. As I anticipated, they make a clamorous demand for more money, even seizing hold of the bicycle and shouting angrily in my face. This I had easily foreseen, and wisely preferred to have their angry demonstrations all to myself, rather than in a crowded city where they could perhaps have excited the mob against me.

For the first time in China I have to appeal to my Smith & Wesson in the interests of peace; without its terrifying possession I should on this occasion undoubtedly have been under the necessity of "wiping up a small section of Kiang-se" with these two worthies in self defence. In the affairs of individuals, as of nations, it sometimes operates to the preservation of peace to be well prepared for war. How many times has this been the case with myself on this journey around the world!

Next: Cycling through China - Part 6

Cycling through China - Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part7 | Part 8 | Around the World on a Bicycle - Maps and Pictures

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.