China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

"Around the World of a Bicycle - Cycling through China in 1886 "

Part 3

Cycling through China - Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part7 | Part 8 | Around the World on a Bicycle - Maps and Pictures

Chao-choo-foo is the next city marked on my itinerary, but as Quang-shi is not on my map I have no means of judging whether Chao-choo-foo is four li up-stream or forty. All attempts to obtain some idea of the distance from the natives result in the utter bewilderment of both questioned and querist. No amount of counting on fingers, or marking on paper, or interrogative arching of eyebrows, or repetition of "Chao-choo-foo li" sheds a glimmer of light on the mind of the most intelligent-looking shopkeeper in Quang-shi concerning my wants. Yet, withal, he courteously bears with my, to him, idiotic pantomime and barbarous pronunciation, and repeats parrot-like after me "Chao-choo-foo li; Chao-choo-foo li" with sundry beaming smiles and friendly smirks.

Far easier, however, is it to make them understand that I want to go to that city by boat. The loquacious owner of a twenty-foot sampan puts in his appearance as soon as my want is ascertained, and favors me with an unpunctuated speech of some five minutes' duration. For fear I shouldn't quite understand the tenor of his remarks, he insists on thrusting his yellow Mongolian phiz within an inch or two of mine own. At the end of five minutes I thrust my fingers in my ears out of sheer consideration for his vocal organs, and turn away; but the next moment he is fronting me again, and repeating himself with ever-increasing volubility. Finding my dulness quite impenetrable, he searches out another loquacious mortal, and by the aid of the tiny beam-scales every Chinaman carries for weighing broken silver, they finally make it understood that for six big rounds (dollars) he will convey me in his boat to Chao-choo-foo. Understanding this, I promptly engage his services.

Bundles of joss-sticks, rice, fish, pork, and a jar of samshoo (rice arrack) are taken aboard, and by ten o'clock we are underway. Two men, named respectively Ah Sum and Yung Po, a woman, and a baby of eighteen months comprise the company aboard. Ah Sum, being but an inconsequential wage-worker, at once assumes the onerous duties of towman; Yung Po, husband, father, and sole proprietor of the sampan, manipulates the rudder, which is in front, and occasionally assists Ah Sum by poling. The boat-wife stands at the stern and regulates the length of the tow-line; the baby puts in the first few hours in wondering contemplation of myself.

The strange river-life of China is all about us; small fishing-boats are everywhere plying their calling. They are constructed with a central chamber full of auger-holes for the free admittance of water, in which the fish are conveyed alive to market, or imprisoned during the owner's pleasure. Big freight sampans float past, propelled by oars if going down-stream, and by the combined efforts of tow-line and poles if against the current. The propelling poles are fitted with neatly carved "crutch- trees" to fit the shoulder; the polers, sometimes numbering as many as a dozen, walk back and forth along side-planks and encourage themselves with cries of "ha-i, ha-i, ha-i." A peculiar and indescribable inflection would lead one, hearing and not seeing these boatmen, to fancy himself listening to a flight of brants in stormy weather. Yung Po, poling by himself, gives utterance to a prolonged cry of "Atta-atta-atta aaoo ii," every time he hustles along the side-plank.

Much of the scenery along the river is lovely in the extreme, and at dark we cast anchor in a smooth, silent reach of the river just within the frowning gateway of a rocky canon. Dark masses of rock tower skyward five hundred feet in a perpendicular wall, casting a dark shadow over the twilight shimmer of the water. In the north, the darksome prospect is invested with a lurid glow, apparently from some large fire; the canon immediately about our anchoring place is alive with moving torches, representing the restless population of the river, and on the banks clustering points of light here and there denote the locality of a village.

The last few miles has been severe work for poor Ah Sum, clambering among rocks fit only for the footsteps of a goat. He sticks to the tow-line manfully to the end, but wading out to the boat when over-heated, causes him to be seized with violent cramps all over; in his agony he rolls about the deck and implores Yung Po to put him out of his misery forthwith. His case is evidently urgent, and Yung Po and his wife proceed to administer the most heroic treatment. Hot samshoo is first poured down his throat and rubbed on his joints, then he is rolled over on his stomach; Yung Po then industriously flagellates him in the. bend of the knees with a flat bamboo, and his wife scrapes him vigorously down the spine with the sharp edge of a porcelain bowl. Ah Sam groans and winces under this barbarous treatment, but with solicitous upbraidings they hold him down until they have scraped and pounded him black and blue, almost from head to foot. Then they turn him over on his back for a change of programme. A thick joint of bamboo, resembling a quart measure, is planted against his stomach; lighted paper is then inserted beneath, and the "cup" held firmly for a moment, when it adheres of its own accord.

This latter instrument is the Chinese equivalent of our cupping-glass; like many other inventions, it was probably in use among them ages before anything of the kind was known to us. Its application to the stomach for the relief of cramps would seem to indicate the possession of drawing powers; I take it to be a substitute for mustard plasters. While the wife attends to this, Yung Po pinches him severely all over the throat and breast, converting all that portion of his anatomy into little blue ridges. By the time they get through with him, his last estate seems a good deal worse than his first, but the change may have saved his life.

Before retiring for the night lighted joss-sticks are stuck in the bow of the sampan, and lighted paper is waved about to propitiate the spirit of the waters and of the night; small saucers of rice, boiled turnip, and peanut-oil are also solemnly presented to the tutelary gods, to enlist their active sympathies as an offset against the fell designs of mischievous spirits. Falling asleep under the soothing influence of these extraordinary precautions for our safety and a supper of rice, ginger, and fresh fish, I slumber peacefully until well under way next morning. Ah Sum is stiff and sore all over, but he bravely returns to his post, and under the combined efforts of pole and tow-line we speed along against a swift current at a pace that is almost visible to the naked eye.

This morning I purchase a splendid trout, weighing seven or eight pounds, for about twenty cents; off this we make a couple of quite excellent meals. Observing my awkward attempts to pick up pieces of fish with the chop-sticks, the good, thoughtful boat-wife takes a bone hair-pin out of her sleek, oily back hair, and offers it to me to use as a fork! Before noon we emerge into a more open country; straight ahead can be seen an eight-storied pagoda. Beaching the pagoda, we pass, on the opposite shore, the town of Yang-tai (?). Fleets of big junks sail gayly down stream, laden with bales and packages of merchandise from Chao-choo-foo, Nam-hung, and other manufacturing points up the river. Others resemble floating hay-ricks, bearing huge cargoes of coarse hay and pine-needles down for the manufacture of paper.

Several war-junks are anchored before Yang-tai; unlike the peaceful (?) merchantmen on the Choo-kiang, they are armed with but a single cannon. They are, however, superior vessels compared with other craft on the river, and are manned with crews of twenty to thirty theatrical-looking characters; rows of muskets and boarding-pikes are observed, and conspicuous above all else are several large and handsome flags of the graceful triangular shape peculiar to China.

The crew of these warlike vessels are uniformed in the gayest of red, and in the middle of their backs and breasts are displayed white "bull's eyes" about twelve inches in diameter. The object of these big white circular patches appears to be the presentation of a suitable place for the conspicuous display of big characters, denoting the district or city to which they belong; or in other words labels. The wicked and sarcastic Fankwaes in the treaty ports, however, render a far different explanation. They say that a Chinese soldier always misses a bull's-eye when he shoots at it- under no circumstances does he score a bull's-eye. Observing this, the authorities concluded that Fankwae soldiers were tarred with the same unhappy feather. With true Asiatic astuteness, they therefore conceived and carried out the brilliant idea of decorating all Celestial warriors with bull's-eyes, front and rear, as a measure of protection against the bullets of the Fankwae soldiers in battle.

Ah Sum becomes sick and weary at noon and is taken aboard, Tung Po and his better half taking alternate turns at the line. Toward evening the river makes a big sweep to the southeast, bringing the prevailing north wind round to our advantage; if advantage it can be called, in blowing us pretty well south when our destination lies north. The sail is hoisted, and the crew confines itself to steering and poling the boat clear of bars.

Poor Ah Sum is subjected to further clinical maltreatment this evening as we lay at anchor before No-foo-gong; while we are eating rice and pork and listening to the sounds of revelry aboard the big passenger junks anchored near by, he is writhing and groaning with pain.

He is too stiff and sore and exhausted to do anything in the morning; the woman goes out to pull, and the babe makes Rome howl, with little intermission, till she comes back. The boat-woman seems an industrious, wifely soul; Yung Po probably paid as high as forty dollars for her; at that price I should say she is a decided bargain. Occasionally, when Yung Po cruelly orders her overboard to take a hand at the tow-line, or to help shove the sampan off a sand ridge, she enters a playful demurrer; but an angry look, an angry word, or a cheerful suggestion of "corporeal suasion," and she hops lightly into the water.

A few miles from No-foo-gong and a rocky precipice towers up on the west shore, something like a thousand feet high. The crackling of fire-crackers innumerable and the report of larger and noisier explosions attract my attention as we gradually crawl up toward it; and coming nearer, flocks of pigeons are observed flying uneasily in and out of caves in the lower levels of the cliff.

In the course of time our sampan arrives opposite and reveals a curious two-storied cave temple, with many gayly dressed people, pleasure sampans, and bamboo rafts. This is the Kum-yam-ngan, a Chinese Buddhist temple dedicated to the Goddess of Mercy. It is the home of flocks of sacred pigeons, and the shrine to which many pilgrims yearly come; the pilgrims manage to keep their feathered friends in a chronic state of trepidation by the agency of fire-crackers and miniature bombs. Outside, under the shelter of the towering cliffs to the' right, are more temples or dwellings of the priests; they present a curious mixture of blue porcelain, rock, and brick which is intensely characteristic of China.

During the day we pass, on the same side of the river, yet another remarkable specimen of man's handiwork on the scene of one of nature's curious rockwork conceptions. Leading from base to summit of a sloping mountain are two perpendicular ridges of rock, looking very much like a couple of walls. Across the summit of the mountain, from wall to wall, some fanciful architect three hundred years ago built a massive battlement; in the middle he left a big round hole, which presents a very curious appearance, and materially heightens the delusion that the whole affair, from foot to summit, is the handiwork of man. This place is known as Tan-tsy-shan, or Bullet Mountain, and is the scene of a fight that occurred some time during the Ming dynasty. A legend is current among the people, that the robber Wong, a celebrated freebooter of that period, while firing on a pursuing party of soldiers, shot this moon- like hole through the mountain battlement with the huge musket he used to slaughter his enemies.

Many huge rafts of pine logs are now encountered floating down stream to the cities of the lower country; numbers of them are sometimes met, following close behind one another. Several huts are erected on each big raft, so that the sight not infrequently suggests a long straggling village floating with the tide. This suggestion is very much heightened by the score or more people engaged in poling, steering, al fresco cooking, etc., aboard each raft.

And anon there come along men, poling with surprising swiftness slender-built craft on which are perched several solemn and important-looking cormorants. These are the celebrated cormorant fishers of the Chinese rivers. Their craft is simply three or four stems of the giant bamboo turned up at the forward end; on this the naked fisherman stands and propels himself by means of a slender pole. His stock-in-trade consists of from four to eight cormorants that balance themselves and smooth their wet wings as the lightsome raft speeds along at the rate of six miles an hour from one fishing ground to another. Arriving at some likely spot the eager aspirant for finny prizes rests on his oars, and allows his aquatic confederates to take to the water in search of their natural prey, the fishes. A ring around the cormorants' necks prevents them swallowing their captives, and previous training teaches them to balance themselves on the propelling pole that the watchful fisherman inserts beneath them the moment they rise to the surface with a fish; captive and captor are then lifted aboard the raft, the cormorant robbed of his prey and hustled quickly off again to business. The sight of these nimble craft, skimming along with scarcely an effort, almost fills me with a resolve to obtain one of them myself and abandon Tung Po and his dreary lack of speed forever.

The third day of our voyage against the prevailing typhoons and the rapid current of the Pi-kiang, comes to an end, and finds us again anchored within the dark shadow of a towering cliff. Anchored alongside us is a big junk freighted with bags of rice and bales of paper; the hands aboard this boat indulge in a lively quarrel, during the evening chow-chow, and bang one another about in the liveliest manner. The peculiar indignation that finds expression in abusive language no doubt reaches its highest state of perfection in the Celestial mind. No other human being is capable of soaring to the height of the Chinaman's falsetto modulations, as he heaps reproaches and cuss-words on his enemy's queue-adorned head. A big boat's crew of naked Chinamen cursing and gesticulating excitedly, advancing and retreating, chasing one another about with billets of wood, knocking things over, and raising Cain generally, in the ghostly glimmer of fantastic paper lanterns, is a spectacle both weird and wild.

Another weird, but this time noiseless, affair is a long string of nocturnal cormorant fishers, each with a big, flaming torch attached to the prow of his raft, propelling themselves along close under the dark frowning cliff. The torches light up the black face of the precipice with a wild glare, and streak the shimmering water with moon-like reflections.

The country through which our watery, serpentine course winds all next day, is hilly rather than mountainous; grassy hills slope down to the water's blue ripples at certain places, but the absence of grazing animals is quite remarkable. Regions, which in other countries would be covered with flocks of sheep and herds of cows and horses, are without so much as a sign of herbivorous animals. Pigs are the prevailing meat-producing animals of Southern China; all the way up country I have not yet seen a single sheep, and but very few cattle; I have also yet to see the first horse. Instead of herbivorous quadrupeds peacefully browsing, are swarms of men, women, and children cutting, bundling, and stacking the grass for the manufacture of paper.

Among the fleeting curiosities of the day are a crowd of sampans flying black flags, evidently some military expedition; they are bound down stream, and it occurs to me that they are perhaps a reinforcement of these famous free-lances going to join the hordes of that denomination making things so uncomfortable for the French in Tonquin and Quang-tse. We also pass a district where the women enhance their physical charms by the aid of broad circular hats that resemble an inverted sieve. The edges, however, are not wood, but circular curtains of black calico; the roof of the hat is bleached bamboo chip.

Officers board us in the evening to search the vessel for dutiable goods; but they find nothing. The privilege of levying customs on salt and opium is farmed out by the government to people in various cities along the rivers. The tax on these articles from first to last of a long river voyage is very heavy, customs being levied at various points; it is scarcely necessary to add that under these arbitrary arrangements, the oily, conscienceless and tsin-loving Celestial boatman has reduced the noble art of smuggling to a science. Yung Po smiles blandly at the officer as he searches carefully every nook and corner of the sampan, even rooting about with a stick in the moderate amount of bilge-water collected between the ribs, and when he is through, dismisses him with an air of innocence and a wealth of politeness that is artfully calculated to secure less rigorous search next time.

The poling and towing is prolonged till nearly midnight, when we cast anchor among a lot of house-boats and miscellaneous craft before a city. Even at this unseemly hour we are visited by an owlish pedlcr, whose boat is fitted up with boxes containing various dishes toothsome to the heathen palates of the water-men. Yung Po and Ah Sum look wistfully over the ancient pastry-ped-ler's wares, and pick out tiny dishes of sweetened rice gruel; this they consume with the same unutterable satisfaction that hungry monkeys display when eating chestnuts, ending the performance by licking the platters. Although the price is nearly a farthing a dish, with wanton prodigality Yung Po orders dishes for the whole company, including even his passenger!

From various indications, it is surmised, as I seek my couch, that the city opposite is Chao-choo-foo. Inquiry to that effect, as usual, elicits nothing but a bland grin from Yung Po. When, however, he takes the unnecessary precaution of warning me not to venture outside the covered sleeping quarters during the night, intimating that I should probably get stabbed if I do, I am pretty well satisfied of our arrival. This cautious proceeding is to be explained by the fact that I am Yung Po's debtor for two days' diet of rice, turnips, and flabby pork, and he is suspicious that I might creep forth in the silence and darkness of the night and leave him in the lurch.

Yung Po now summons his entire pantomimic ability, to inform me that Chao-choo-foo is still some distance up the river, at all events that is my interpretation of his words and gestures. On this supposition I enter no objections when he bids me accompany him to the market and purchase a new supply of provisions for the remainder of the journey.

Impatient to proceed to Chao-choo-foo I now motion for them to make a start. Yung Po points to the frowning walls of the city we have just visited, and blandly says, "Chao-choo-foo." Having accomplished his purpose of bamboozling me into replenishing his larder, by making me believe our destination is yet farther upstream, he now turns round and tells me that we have already arrived. The neat little advantage he has just been taking of my ignorance with such brilliant results to the larder of the boat, has visibly stimulated his cupidity, and he now brazenly demands the payment- of filthy lucre, making a circular hole with his thumb and finger to intimate big rounds in contradistinction to mere tsin.

The assumption of dense ignorance has not been without its advantages at various times on my journey around the world, and regarding Yung Po's gestures with a blankety blank stare, I order him to proceed up stream to Chao-choo-foo. The result of my refusal to be further bamboozled by the wily Yung Po, without knowing something of what I am doing, is that I am shortly threading the mazy alleyways of Chao-choo-foo with Ah Sum and Yung Po for escort. What the object of this visit may be I haven't the remotest idea, unless we are proceeding to the quarters of some official to have my passport seen to, or to try and enlighten my understanding in regard to Yung Po's claims for battered Mexican dollars.

Vague apprehensions arise that, peradventure, the six dollars paid at Quang-shi was only a small advance on the cost of my passage up, and that Yung Po is now piloting me to an official to establish his just claims upon pretty much all the money I have with me. Ignorant of the proper rate of boat-hire, disquieting visions of having to retreat to Canton for the lack of money to pay the expenses of the journey through to Kui-kiang are flitting through my mind as I follow the pendulous motions of Yung Po's pig-tail along the streets. The office that I have been conjuring up in my mind is reached at last, and found to be a neat room provided with forms and a pulpit like desk.

A pleasant-faced little Chinaman in a blue silk gown is examining a sheet of written characters through the medium of a pair of tortoise-shell spectacles. On the wall I am agreeably astonished to see a chromo of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, with an inscription in Chinese characters. The little man chin-chins (salaams) heartily, removes his spectacles and addresses me in a musical tone of voice. Yung Po explains obsequiously that my understanding Chinese is conspicuously unequal to the occasion, a fact that at once becomes apparent to the man in blue silk; whereupon he quickly substitutes written words for spoken ones and presents me the paper. Finding me equally foggy in regard to these, he excuses my ignorance with a courteous smile and bow, and summons a gray-queued underling to whom he gives certain directions. This person leads the way out and motions for me to follow. Yung Po and Ah Sum bring up behind, keeping in order such irrepressibles as endeavor to peer too obtrusively into my face.

Soon we arrive at a quarter with big monstrous dragons painted on the walls, and other indications of an official residence; palanquin-bearers in red jackets and hats with tassels of red horse-hair flit past at a fox-trot with a covered palanquin, preceded by noisy gong-beaters and a gayly comparisoned pony. This is evidently the yamen or mandarin's quarter, and here we halt before a door, while our guide enters another one, and disappears. The door before us is opened cautiously by a Celestial who looks out and bestows upon mo a friendly smile. A curly black dog emerges from between his legs and presents himself with much wagging of tail and other manifestations of canine delight.

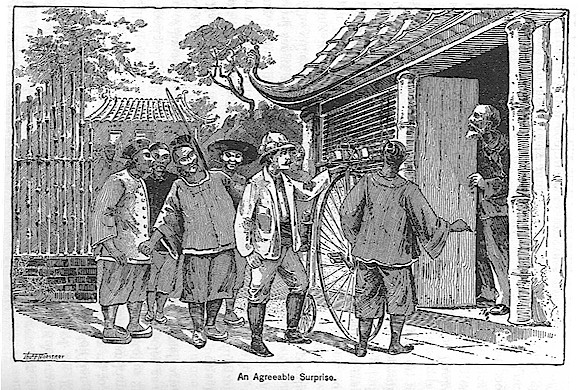

All this occurs to me as very strange; but not for a moment does it prepare me for the agreeable surprise that now presents itself in the appearance of a young Englishman at the door. It would be difficult to say which of us is the most surprised at the other's appearance. Mutual explanations follow, and then I learn that, all unsuspected by me, two missionaries of the English Presbyterian mission are stationed at Chao- choo.

At Canton I was told that I wouldn't see a European face nor hear an English word between that city and Kui-kiang. On their part, they have read in English papers of my intended tour through China, but never expected to see me coming through Chao-choo-foo.

I am, of course, overjoyed at the opportunity presented by their knowledge of the language to arrange for the continuation of my journey in a manner to know something about what I am doing. They are starting down the river for Canton to-morrow, so that 1 am very fortunate in having arrived to- day. As their guest for the day I obtain an agreeable change of diet from the swashy preparations aboard the sampan, and learn much valuable information about the nature of the country ahead from their servants. They have never been higher up the river than Chao-choo-foo themselves, and rather surprise me by giving the distances to Canton as two hundred and eighty miles.

By their kind offices I am able to make arrangements for a couple of coolies to carry the bicycle over the Mae-ling Mountains as far as the city of Nam-ngan on the head waters of the Kan-kiang, whence, if necessary, I can descend into the Yang-tsi-kiangby river. The route leads through a mountainous country up to the Mae-ling Pass, thence down to the head waters of the Kan-kiang.

All is ready by eight o'clock on the morning of October 22d; the coolies have lashed the bicycle to parallel bamboo poles, as also a tin of lunch biscuits, a tin of salmon, and of corned beef, articles kindly presented by the missionaries.

Nam-ngan is said to be two hundred miles distant, but subsequent experience would lessen the distance by about fifty miles. Our -way leads first through the cemeteries of Chao-choo-foo, and along little winding stone- ways through the fields leading, in a general sense, along the right bank of the Pi-kiang.

The villagers in the upper districts of Quang-tung are peculiarly wanting in facial attractiveness; in some of the villages on the Upper Pi-kiang the entire population, from puling infants to decrepit old stagers whose hoary cues are real pig-tails in respect to size, are hideously ugly. They seem to be simple, primitive people, bent on satisfying their curiosity; but in the pursuit of this they are, if anything, somewhat more considerate or more conservative than the Persians.

Mothers hurry home and fetch their babies to see the Fankwae, pointing me out to their notice, very much like pointing out a chimpanzee in the Zoological gardens. In these village inns the spirit of democracy embraces all living things; sore-eyed coolies, leprous hangers-on to the thread of life, matronly sows and mangy dogs, come, go, and freely mingle and associate in these filthy little hittims. When cooking is in progress, nothing is set off the fire on to the ground but that a hungry pig stands and eyes it wistfully, but sundry burnings of their sensitive snouts during the days of their youthful inexperience have made them preternaturally cautious, so that they are not very meddlesome. The sleeping room is really a part of the pig-sty, nothing but an open railing separating pigs and people. A cobble-stone path now leads through a hilly country, divided up into little rice-fields, peanut gardens, pine copses, and cemeteries. Peanut stalls one encounters at short intervals, where ancient dames or wrinkled old men preside over little saucers of half-roasted nuts, peanut sweet cakes, peanut plain cakes, peanut crullers, peanut dough, peanut candy, peanuts sprinkled with sugar, peanuts sprinkled with salt, and peanuts fresh from the ground. The people seem to be well- nigh living on peanuts, which unhappy diet probably has something to do with their marvellous ugliness.

In a gathering of villagers standing about me are people with eyes that are pitched at the most peculiar angles, varying from long, narrow eyes that slope downward toward the cheek-bone, to others that seem almost perpendicular. No less astonishing is the contour of their mouths; ragged holes in their ugly faces are these for the most part, shapeless and uncouth as anything well could be. They are the most unprepossessing humans I have seen the whole world round.

Next: Cycling through China - Part 4

Cycling through China - Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part7 | Part 8 | Around the World on a Bicycle - Maps and Pictures

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.