China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

Danielle R. Reed

Cycling in Western Sichuan

Copyright © Danielle R. Reed, 2002.

Part 3

They were the best of roads, they were the worst of roads.

Good roads in China are smooth, swept, free of holes and a pleasure to ride along. Bad roads in China are dirt ruts full of rocks, dust and mud. I never saw a good road that didn’t look brand new, and the bad roads look like they have been there for three thousand years. My bike was a hybrid without front suspension, but I would have worried less and been more confident with a more rugged mountain bike fitted with tires with deep tread. Road bikes and touring bikes will not do, unless you are positive that there will be only high quality roads. Given the fast pace of construction in China, there is almost no way you can predict what road surfaces you might find, so the mountain bike is the safe choice.

I spend time trying to incorporate bike riding into business or work-related travel, so, rather than carry around a big bike case, I decided to get a bike that unscrews and fits into a suitcase. Steve Bilenky at Artistry in Steel made me a bike that fits into a suitcase small enough to be checked as regular luggage by most airlines.

Although I love the color, I wrestled with the bike when getting both in and out of the suitcase. I am not mechanically inclined, and when my husband first explained the concept of a bike that fits into a suitcase, I had an idea that I would push a discrete button on the bike, and it would fold itself up in a puff of smoke and be stowed neatly away. It doesn’t quite work like that.

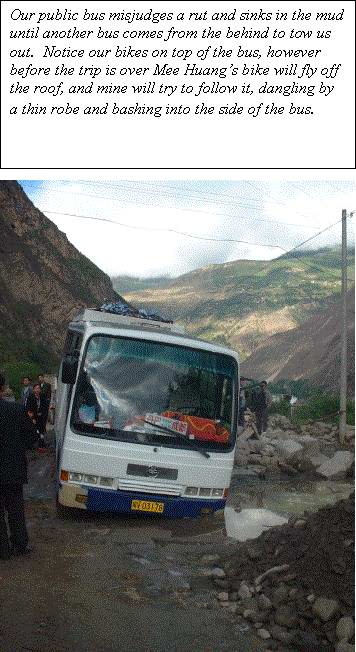

This is my "unscrewable" bike that fits into a suitcase. If you look closely, you can see evidence of poor bike nutrition (i.e., the half-empty Pepsi bottle). The handlebars are still in good shape but this would change after the bike fell off the roof of the bus on the return trip from Danba. Mee Huang’s bike fell off first and took the brunt of punishment. She fared less well, with a taco’d wheel and rim.

Rules of good bike nutrition flew out the window.

Although extreme views about sports nutrition exist, there are some basic rules to which most people subscribe. I violated the basic rules, and paid the price. First of all, there are no sports beverages in rural China, and so the drink choices are Pepsi, orange soda, a yellow drink that looked like urine, bottled water and tea. You can construct from those options suitable hydration for long bike rides, but two factors kept me from drinking enough fluid. First of all, frequent drinking means frequent bathroom stops, and this was something I wanted to avoid because of the filthy toilets. A note to the men reading this monograph—you may not have the advantages you think. Although the sanitation is poor by U.S. standards, I never saw a man urinate out of doors, and my interpretation of the frequent number of rural toilets is that al fresco bathroom breaks is poor form, even for men working in fields and forests. My second problem, which kept me from drinking enough fluid, was the unexpected nausea and extreme fatigue. It reminded me of the way I felt during the first three months of pregnancy. Putting anything near my mouth, even my toothbrush, revolted me, and I had to force myself to drink even a little bit. This problem resolved when I adapted to the altitude (up to 14k feet), and is evidently common among people who go up too far, too fast.

The available food posed challenges but also provided bright spots. Americans cherish a hope that when they visit somewhere new, they will be able to eat the locally grown or caught foods. For instance, if you go to the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, you hope to eat fresh, locally caught crabs. American tourists are often disappointed because refrigeration and freezing of foods is pervasive, and your seafood dinner in Maryland is likely to have been caught thousands of miles away and frozen. Similarly, Americans like their ethnic cuisine authentic and criticize the American versions of foods: Taco Bell is not real Mexican food and the corner Chinese restaurant does not offer real Chinese food. I am reminding you of these details as a way of prefacing what is good about rural China. There is little or no refrigeration, and the food you eat is all grown locally and fresh, at least in the sense that it has just been picked or killed. And if you have been searching for authentic Chinese cuisine all your life, you can relax. You found it.

This situation has a downside: no matter how hard you search, you will only be offered authentic Chinese food. There are no other choices. In rural China, you do not swing into McDonalds for fries and a cup of coffee. Since neither Mee Huang nor I can read a Chinese menu, she would go into the kitchen, see what food they had, point out what looked good, and asked the cook to prepare it. This is system that worked well for me because I never had to look at the kitchen and every meal was a surprise. Mee Huang, however, bore two burdens: she never complained about the kitchens, but I am sure that she saw bits of dead animals and filth. Second, she had to find something that I could eat when faced with few choices. Mee Huang is a vegetarian and I am not an enthusiastic carnivore, and it seemed best to avoid all meat products, especially after seeing the windows of tripe and chicken feet displayed in the markets. We ate vegetables, noodles and rice and sometimes eggs and tofu. Although good sports nutrition would dictate frequent small meals, it is not feasible when biking in rural China. There is no way to put rice and vegetables in your back pocket for later. There is some snack food, like packaged cookies, but it is stale and overpriced, and never looks appealing enough to buy unless you are starving.

Chinese food for lunch and dinner is common in the U.S., but a Chinese breakfast was alien and unappetizing. After several attempts, I did learn to pick my way through a typical Chinese breakfast. In the more sophisticated places we stayed, we were offered porridge of watery rice, little buns of bland white bread, peanuts, fermented tofu, fermented cabbage and tea. This seemed to be a standard breakfast in the same way that you would go to a Denny’s in the U.S. and get bacon, eggs, toast and coffee. The shock for me was eating rice porridge with no salt, butter, sugar or jam. It was too bland, and tasted like something you would feed a sick baby. The bland buns of bread, when filled with peanuts, could almost pass as an American style peanut butter sandwich, and became a staple food item for me. The fermented tofu tasted like a well-matured Stilton cheese, which I enjoy, but not for breakfast. I gave a wide berth to the pickled cabbage, and noticed that the Chinese diners did too. My guess was the proportion of Chinese who eat the pickled cabbage for breakfast is the same as the number of Americans who eat the parsley decoration served on restaurant meals.

We were cycling in Sichuan Province, which is famous for its spicy food. I like spicy food and I was disappointed because the cooks would hear from the waitresses that I was a White Foreigner and then would not add chili to my food. We sometimes suspected the cook would add my extra chili into Mee Huang’s food to make p the deficit, which made her mouth burn and her stomach upset. Occasionally, cooks and waitresses would make an attempt to give me something they thought a White Foreigner would enjoy—I was happier than you might imagine to have strawberry jam one morning for breakfast, and a kind cook made me French Fries with catsup on another occasion.

A word about my drug of choice.

During the first three days of the bike trip, I felt progressively worse and worse, so much so that I became scared. I felt sick but I didn’t know why. As it turns out, it was altitude sickness, but at the time, I attributed it to the lack of coffee. In Shanghai, at the luxury hotel, there was plenty of coffee but as we moved further and further into the mountains, coffee was non-existent. However, at the nadir of my illness, Mee Huang discovered powered "Nescafe", which is sold at extortionate prices and is composed of instant coffee, chemical cream, and sugar, and is sold in powered form. My lust for coffee was intense, and I developed an understanding about the base nature of the drug addict. The coffee did not cure my altitude sickness but it did make me happy.

A word about the Chinese drug of choice.

I am unsure if the tea drunk by the average Chinese person has any type of psychoactive drugs in it, but I assume it does because people drink tea the same way that Americans drink coffee. Chinese workers have a metal, plastic or glass cup, not unlike an American style coffee cup designed to accompany you in the car, and they take their cup everywhere they go. There are constant refills of water for the tea, and tea is sipped morning, noon, and night. It is always tea-time in China. I assume that tea must be an addictive substance, otherwise, no one would go to the trouble to heat the water. Frankly, it didn’t do anything for me, and did not damp my thirst for coffee.

Danielle R. Reed - Cycling in Western Sichuan: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.