China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

"Uighurs and Other Friends:

A Xinjiang Travel Experience"

August 1998

Page 1

Copyright © John McHale, 2002.

Skip to: John McHale - Page 1 | John McHale - Page 2 | John McHale - Page 3

PROLOGUE

I’m sitting in a hospital bed in Hongkong with forty-one stitches in my head and taking stock of things.

This means yet another delay to my Karakoram trip. I’m also worried about the inevitable scar on my head. I try to imagine that it will end up looking rather staunch, but when I look in the mirror the reality is just plain ugly.

I still haven’t decided what the lesson is here. Maybe something along the lines of: "when biking down steps along a cliff edge, don’t let bees fly into your mouth"…?? I went over head-first, and it’s obvious that my helmet saved my life.

A week later I go back to the scene of the accident to try to find my glasses. I know they were smashed because the surgeons found glass fragments in the wound. It’s easy to see where I fell, as there is still lots of my blood splattered around the place, and it’s a little spooky.

I eventually find my glasses at the bottom of the cliff where I landed five metres below. The frame is mangled and minus one lens, but salvageable. The climb back up is tricky, and I can’t imagine how I did it in my previous, semi-dazed state. I still have no memory of it. Only a vague recollection of cycling home, and the horrified expressions from various people along the way. Then my own feelings of horror when I finally get home and see what I’ve done to myself. My skull was exposed in two places, and it wasn’t until I was eventually stitched up that I dared to look in the mirror again.

After leaving hospital I spend the week preparing for my trip, and enjoying the sympathy of friends. I discover that women really have a thing about guys with bandages. It really brings out their maternal instincts. The effect is entirely the opposite once the bandage finally comes off, and it seems quite appropriate that I should now head off into the middle of nowhere.

DAY 1 : HONGKONG – GUANGZHOU – URUMQI 12 August 1998

On the day of my departure from Hongkong it is raining. I have a sense of apprehension as I load my bike into the taxi. It doesn’t feel like I’m going on holiday. Certainly it’s not a holiday in the normal sense, like lazing on a beach in Thailand. Admittedly, that kind of holiday has never appealed to me, although I have no illusions about China - it’s hard work. I consider briefly the possibility of going somewhere else….somewhere easier. I wonder if anyone would find out? But eventually I arrive at the KCR. Getting on the through train to Guangzhou is very easy and efficient, and my resistance gradually evaporates.

It’s obvious on arrival that Guangzhou has changed enormously since my first visit in 1990, and it’s clear also that China has been learning English much faster than I have been learning Chinese. Many people seem to have a basic grasp of the language, which, like so many other things in Guangzhou, is motivated by the pursuit of profit. As a result, I feel self-conscious about saying anything in Chinese.

Coming out of the railway station with my bike I am surrounded in the usual fashion by transport touts. I feel more comfortable asking directions from those who don’t speak English, although my attempts to speak Chinese still sound clumsy and stilted. I think to myself that I really must settle down one day to learn this language properly. My half knowledge often gets me into far more trouble.

Guangzhou Airport is a very busy place and seems to operate more like a bus station. I’m hoping to catch the earlier flight to Urumqi. The alternative is a long wait and then an extended flight via Beijing which arrives in Urumqi at 1 a.m. I ask at the counter nervously You mei you kongwei?…Excellent, there are still seats! In my excitement I forget to let down the tyre pressure and the bike disappears down the conveyor belt along with the other suitcases. I’m never happy about the way airlines treat a bike as just another piece of luggage to be banged around, but I’m relieved all the same.

While waiting for the departure I chat with another westerner who is visiting China for the first time. We spend most of the time talking about snowboarding of all things. He’s doing one of the popular tourist routes: Guangzhou – Guilin – Yangshuo, which serves as the "China Experience" for many foreigners. I eventually say good-bye and I’m soon onboard the plane waiting for takeoff. The air-hostesses look beautiful and bored. One of them glances at me in a way that suggests my two week old scar really is looking like the result of a lobotomy.

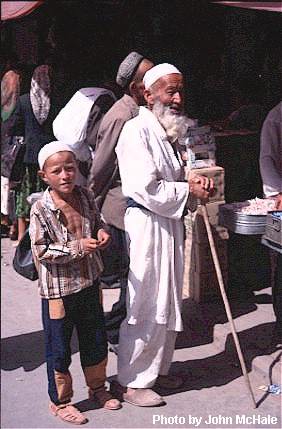

The concerns about my appearance are quickly put aside however, as I’m starting to feel excited about my trip again. I recall what I have read about the area I am going to: Xinjiang, the far-western reaches of China, where the Uighur/Turkic minorities represent the transition from China to Central Asia. There is a fabulous history of this area told by Peter Hopkirk, along with stories of the colourful Sunday bazaar in Kashgar, where nomad warriors ride into town carrying weapons, in much the same way they did hundreds of years ago.

Two hours into the flight we leave Central China and the clouds finally clear. We are over a bizarre landscape that resembles a vast wood carving with sharply chiselled terraces. The contour relief in the evening light is so striking. We then pass over the awesome Yellow River, which is in fact a deep pink, and flanked on either side by a continuous lining of green farmland. Then what must be the city of Lanzhou, which appears dry and barren, and is setout with rigid, military precision.

We continue over an area of incredible emptiness – like a lunar landscape. I have never seen anything like this before, and I spend the remainder of the flight completely captivated by the view. Then suddenly there appears a straight line of red/brown mountains running endlessly from north to south. Nowhere have I seen a more precise and clearly defined fault line than here in this featureless desert. We pass over these mountains, and on the other side there is an even more striking nothingness: just a vast, windblown flatness where the only features are the clouds and their direct shadows on a two-dimensional landscape. How can anything be so continuously empty? This is the famous Gobi Desert, and it has me transfixed for over an hour.

Finally, we pass over another confined band of mountains and land in Urumqi on the plains beyond. As I enter the airport building I see the luggage attendants in the distance taking turns on the bike. I smile with relief, since it means that not only is the bike here, but it’s still in working order. I pick up the bike from an excited Chinese man waiting in the baggage reclaim area, and he gives me a thumbs up saying in English "good bike! good bike!". It’s a nice welcome to Urumqi.

At the Hongshan Hotel I meet two Korean girls who are having a break from Chinese study in Qingdao. It’s a pleasant opportunity for further Chinese practice since they don’t speak English. Later that evening a walk through the streets provides a glimpse of the harsh reality of life in this isolated city in the far North-West of China. I go back to the hotel feeling tired. There seems little of interest in Urumqi itself. I remind myself that my only purpose here is to visit Heaven Lake 50 kilometres outside of town, and then fly onward to Kashi, which marks the beginning of the Karakoram Highway.

DAY 2 : HEAVEN LAKE 13 August 1998

Tianqi bu hao…….it’s raining. I’m supposed to go to Heaven Lake with the two Korean girls, but I’m up late and I resign myself to catching a later bus. I have breakfast at the Holiday Inn down the road, and can’t help feeling like a pampered wimp. Among other things, it’s taking me a while to adjust again to the local toilet standards, and I’m pre-occupied by the issue of where to buy toilet paper. It’s difficult to find anyone who sells this stuff on the street, and I notice that the toilet rolls in the Holiday Inn are screwfixed tightly to the holders. I’m obviously not the first scruffy westerner to come in here with the thought of stealing some for the days ahead.

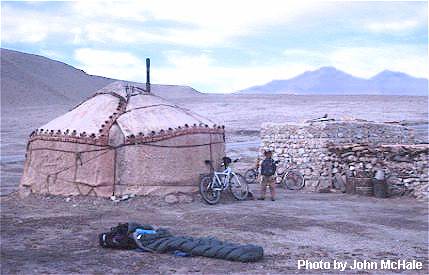

I eventually catch a bus to Heaven Lake. It’s a pleasant two hour trip, and the weather slowly improves. On arrival it immediately strikes me that Heaven Lake was clearly a beautiful, unspoilt place at one time. Like so many of the world’s nature spots, the commercial aspects of tourism generally makes a mess of things. Tourism though is the only means of livelihood for the locals who live within yurts along the lakeside. Although many of the tourists arrive in tour buses and only stay a few hours at a time, the attraction for many foreigners and local travellers is to stay overnight in these yurts.

In between tour buses Heaven Lake does take on a sudden tranquility, which after three years living in Hongkong, seems a little unsettling. I’m not used to quiet places and the lack of amenities. The locals here are so poor. For Y40 you get to stay one night in a smelly, mosquito infested tent, complete with three dubious looking meals. Still fresh out of a modern, western environment, these yurt communities seem like miserable, uncomfortable places, and I spend a long time trying to decide if this is really an experience that I will treasure.

An old man shows me the way around the lake in the hope that I will stay with his family. He points out his six-year old grand-daughter who is waving next to a yurt in the distance. I nod my head and shake his hand, and he goes back in the hope of finding more tourists.

The final stretch around the lake becomes a bit difficult, and I convince myself (maybe too easily) that it’s not worth it. I go back to another yurt in the nearer bay and chat with two American girls. Gia and Christina are travelling around Xinjiang before starting their English teaching jobs in Shanghai, and are staying for the yurt plus horse-riding package. I’m tempted to join them. But the grand-daughter sees me, and nimbly races around from the next bay to remind me where her family yurt is.

I’m in a kind of dilemna. Certainly if I was going to stay I would prefer to remain with the Americans, but the anxious look on the little girl’s face seems so pitiful. Eventually however, I decide to catch the final bus back to Urumqi that afternoon: rather than disappoint the little girl and her family by staying at a different yurt.

Back at the hotel in Urumqi that evening I’m anxious to get a view of the sunset and the now distant, snow covered mountains. A young tourism student: "Li WuShi" kindly goes out of her way to show me a good viewpoint. Naturally she is hoping I will buy a tour from her, but she seems genuinely interested in my efforts to learn Chinese. I don’t see the mountains, but the sunset makes Urumqi seem less like a garbage dump. I’m excited about the thought of getting to Kashgar (Kashi) tomorrow.

That evening, the hotel workers have a great time racing up and down the corridors on my bike. But eventually it’s time for me to go to bed, and like a strict parent, I disappoint them by putting the bike away.

DAY 3 : URUMQI - KASHI 14 August 1998

I leave early in the morning and take a taxi to the airport. But on arrival I discover no morning flight to Kashi – how stupid of me! Why didn’t I ring to check?? Anyway, I manage to book myself on a flight at 7.00 pm that night. I have breakfast near the airport and try to decide what to do for 12 hours. It occurs to me that I’ve been slow to get back into the habit of scrutinising prices and bargaining, but I start to pay more attention to this after noting what locals are paying alongside me.

I decide to use my bike for the first time since arriving in China and plan to cycle the 20 kms back to town. I’m nervous about cycling again after the accident and take a long time preparing, but eventually I’m off. It’s a beautiful morning, and gliding along a pleasant tree-lined lane with the sunlight peeking through the leaves, my trip already seems worthwhile. I’m reminded of how cycling can be a very relaxing way to travel in China.

I say "ni hao" to a pretty girl as I pass by, and she flashes an amazing smile and says "hi". I take a few photos along the way and amble on with my walkman going. I have more breakfast at a roadside stall – this time I’m paying the same as the locals.

It takes me two hours to get back to town, and still pampering myself, I have a decadent western lunch and beer at the Holiday Inn. I’m now feeling satisfied in preparation for the return trip to the airport. The beautiful weather continues through the afternoon as I cycle back.

The airport is now crowded with evening passengers and there is a sense of stress and chaos everywhere. A shy Uighur kid peeks out from behind his mother and seems transfixed by my bike. I lower the seat and encourage him to try riding it around the terminal. Nothing like provoking airport authority with a harmless bit of fun, and it somehow helps to take the nervous edge off things.

During the flight the view of the mountains is fabulous – these are real mountains with permanent snow and form the beginnings of the Karakorams separating China , Pakistan and Uzbekistan. I’m now getting more of a sense of being in a barren, wild place which is so different from anywhere else I’ve been. From 30 000 feet I see smoke from one or two nomadic campfires – how do people survive in this hostile terrain?, what do they eat? There’s no vegetation.!?

I cycle fast from the airport into the Kashi township attracting a lot of attention along the way. It’s 9.30 pm (Beijing Time) but still light, although I’m worried that it’s going to rain. I ask directions along the way. The Uighurs seem like very relaxed, friendly people. Eventually I arrive at the Seman Hotel: "One of the Ten Best Hotels in the World". The stupid thing is they really believe it, and I guess it demonstrates their limited view of the world which probably only extends as far as Urumqi.

I check into the dorm and chat to a Japanese person already there. He doesn’t speak English but we communicate at a basic level in Chinese. I’m amazed at how many Japanese are studying Chinese. "Ishigawa" is a nice guy who deals in tea/coffee products from Xiamen. He gives me a bag of filter coffee and filters, and the idea of real coffee in a place like this seems like heaven.

Eventually I get into the shower. It’s grubby and dark, but ok. I’m not sure then exactly what happened….maybe as I turned to face the taps, or while I had my face covered in shampoo, but suddenly I notice that my waist bag is missing. I’m stunned, and in a nervous panic I run in and out of the shower area like an idiot. I remember someone coming into the shower area to use the toilet next door, but now there’s no sign of anyone. I try to imagine that it’s fallen somewhere or just been mislaid, and I search frantically. But then I start to feel numb as reality slowly bites.

- Two passports, all money, visa card – everything gone.

I’ve heard of things like this happening – this time it’s me, and I can’t imagine anywhere worse. I go down to the Hotel reception and tell them what has happened. They say all phones are down because of the flooding in Central China and that I should call the police tomorrow morning. They don’t seem to care. No embassies, no police available. As far as bad situations go it doesn’t get much worse than this. I suddenly realise how vital these things are to my survival. What happens now? Do I end up dying here? No sleep that night.

DAY 4 : KASHI 15 August 1998

I’m up early but the hotel reception tells me the phones are still down and that the police will be on holiday for two days – I’m hungry, not having had dinner the night before. It seems ridiculous that there are no police available. One of the few people who seems willing to help is a 21 year old Uighur graduate who works at the hotel. "Ani" shows me the way to a police station in the hope that I can get a police report filed for insurance purposes. That’s really all I need the police for, and according to my insurance policy the theft needs to be reported within 24 hours.

The two policemen at the station aren’t the slightest bit interested in my situation. As far as they’re concerned it’s a public holiday for two days, and are clearly annoyed that they are the ones who have to work during this time ….so what happens if someone gets murdered??!! …does nothing happen for two days?? I’m obviously dealing with the wrong people here.

On the way back Ani buys me a muslim breakfast of bread and milk. I’m worried about the hygiene of the restaurant, but I’m grateful, and too hungry to resist anyway. Right now I need a friend. The most important thing at this stage is to cancel my visa card. It’s seems that the hotel are not interested in letting me use their phone. They’re concerned about the cost and my inability to pay. I need to get into contact with my Hongkong flatmate: Nigel, who is the only one who can help. If I can get through to him he should be able to sort everything out, including making contact with the embassies . He’ll be at work now – what the hell is his phone/fax number??

After a limbo period at the hotel of two hours another Uighur man: "Muntsillop" offers to take me to the post office where I can use the phones – I’ve decided I really like the Uighurs. When we get there the phones are clearly working but connections are unreliable. Miraculously, I get through to Hongkong straight away. I’m confused when "Ayty" our filipino maid answers. But then I remember it’s Saturday morning. Her English isn’t that great and the desperation in my voice must have freaked her a bit. I leave a voicemail message for Nigel also, but it still seems inconclusive.

This Uighur man is very talkative. As we walk back I try to follow his Chinese, and understand what he is saying, although I can’t help being pre-occupied with my own situation. Everything depends on the success of that phone call. It seems Muntsillop is hoping to be accepted into a British University. I wonder if he has any concept of how expensive London is? But he has been so kind. He left his watch as part payment for the phone calls. He says he is leaving town soon and I tell him to give me his address so I can send the money to him. He says it doesn’t matter, but eventually he gives me a pager number.

Back at the Hotel I decide that I can’t rely on the Hotel to help me. I refuse to believe there are no police available and go off in search on my own. After asking directions from a military post I find another small police office where a couple of officers are lounging around in their singlets watching TV. These guys clearly don’t want to be disturbed, and after explaining to them what has happened I wait and wait, becoming more depressed. I wonder if they fully understand my Chinese, but I note they are making phone calls.

My brain is spinning – Nigel has to cancel my visa card. That is the most important thing. It’s 2.30 pm and I’m feeling very hungry again. I wonder what it’s like to starve to death: probably very uncomfortable. The irony is that if this hadn’t happened I would probably be really enjoying Kashi. What a waste! I try to imagine if I have ever been in a worse situation – I can’t.

Finally after an hour someone indicates that something is happening. I continue to wait. There is plenty of time to reflect on things, and I torment myself with the now obvious flaws in my preparation for this trip.

I had three separate items:

- a wallet under my shirt containing one passport, US dollars, Visa card, and HKID card.

- a waist bag with one passport, US dollars, HK dollars, RMB, and Visa phone no.

- a wallet in my pocket with small denominations of RMB.

During my infamous shower I momentarily combined all three and put them on the window ledge immediately next to the shower. All I have now is a photocopy of my NZ passport, but not of my Chinese or Pakistan visa. Now there is only one way out of here – back via Urumqi.

Mistake No. 1: should have locked door to shower/toilet area – but of course I didn’t want to restrict anyone’s access to the toilets.

Mistake No. 2: should have kept things separate - even taking the risk of leaving something in the dorm would have been better.

Mistake No.3: should have been suspicious of the person that came in, and should not have taken my eyes off my things for a second.

What happens next seems ludricrous, and would be funny if I was in the mood. Another Police Officer turns up looking like he’s just woken up. He tells me we are going back to the Hotel, and that I should follow him. Then he gets on his bicycle and beckons me to trot after him in the 30 degree heat. Sweating, I eventually arrive at a different Hotel which is also called the "Seman" hotel, but at least there are indications that I’m finally being taken seriously. There are two military vehicles and five young soldiers waiting. One looks like a banana republic general, and one is in full camouflage gear. Great guys.….but wrong hotel!

Finally we get to the right hotel, and for the third time I explain what has happened. On seeing these official looking people the hotel also starts to take my situation a little more seriously. But I’m starting to feel a little frustrated by the disorganisation of these guys. After a lot of endless milling around, two plain clothes policemen finally turn up and to my relief seem to have a much more professional attitude. They take photos and begin preparing a formal report. They tell me I don’t need to use Chinese anymore. They are the Foreign Service Police and one of them has good English.

For the first time since the incident I’m beginning to feel there might be a way out of this situation. The hotel is requested to let me stay and run up a tab until money arrives, and in deference to the police they agree. It takes a lot more convincing, but finally they also agree to let me use the phone in the Business Centre. Before I was simply told: dianhua huaile (phone doesn’t work).

Such a relief to talk to Nigel. As expected he’s on the ball and things are in motion, although it sounds like it will take a while for money to get here – maybe up to two weeks! Nobody it seems, including the banks, have ever heard of this part of the world, and how money gets transferred here is a big question. I’ll try ringing Nigel again tonight. I’m beginning to feel more resigned and philosophical about my situation now, and it no longer seems life threatening. Maybe I can have a wander round tonight and pretend this is still a holiday..?

Ishigawa my Japanese room-mate has gone, but he has left me apples and biscuits, along with the coffee. What a nice guy. I knew he was sympathetic, but also a bit embarrassed about the whole thing. There is now another Japanese guy in the dorm, but since he doesn’t speak English or Chinese we don’t communicate much beyond smiling.

Later that evening I get a fax from the British Consulate in Beijing. This is great – they know about my situation and are switched on to the Kashi scene. The fax somehow gives extra validity to my situation and the staff in the hotel suddenly adopt me as if I’m some famous movie star! Many of the staff there seem genuinely concerned, although I’m still feeling generally resentful towards the management, particularly the painted tart who runs the Business Centre, who previously was so uncooperative. She now seems especially obsequious, and for some reason starts fawning on me:

Ni ji tsui?…..ni jiehuan le ma?…..ni you mei you nu pengyou?

It’s agreed that the hotel restaurant will feed me three meals a day for Y40…..a bargain! My first dinner that night is overwhelming. I count eleven dishes plus rice and beer. In fact the waitresses fall over themselves to feed me. Certainly I’m hungry but they must imagine me to be near death. My stomach is so small I fill up within minutes. Hen baoqian, wo yijing bao le!.

I feel embarrassed by their overly attentive service, and it seems that whether I like it or not I’m going to be fed three large meals a day for the entire period. I try to escape as soon as possible.

As the sun sets a sandstorm hits town and really highlights the isolation of this place. It occurs to me that my Chinese has improved enormously since the incident. Clearly by necessity. I spend the evening sitting in the "groovy" traveller’s caf? across the road, while my stomach starts to lurch threateningly. I remember that I had to use the restaurant chopsticks as mine were among the stolen items. I can now imagine the bacterial count in my gut slowly reaching critical mass, and a possible meltdown in my underpants. It seems only a matter of time.

Tomorrow is the famous Sunday Market, so hopefully that will take my mind off things. I know that pickpockets are a feature of the market, and I take comfort in the fact that I now have nothing for anyone to steal.

Skip to: John McHale - Page 1 | John McHale - Page 2 | John McHale - Page 3

Bike China Adventures

Main Page | Guided Tours

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, 1998-2005. All rights reserved.