China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

Guinness Book of Records holder

"Epic Journeys"

Copyright © Heinz Stücke, 2000.

Introduction

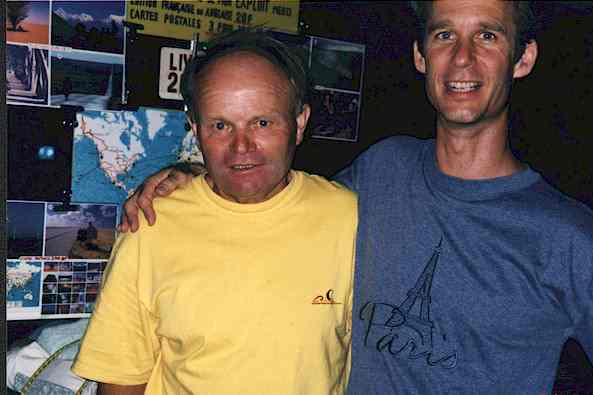

I have been hearing about Heinz Stücke for more than 10 years. While I was on my my three-year bike tour, people I met would tell my about Heinz and that I should meet him. Well, after ten years of looking, I finally found Heinz in Paris on the sidewalk selling his brochures that I had heard so much about. Also with him was his long-time girlfriend Zoya, who he afectionately calls "Zoya, the destroya" for her tendency to sidetrack Heinz from his mission in life to seek out new places to travel to on his trusty three-speed bike that he has used since the 1960's. Needless to say, he didn't know me from Adam, but we quickly got to know each other from our common interest in both international cycling and exotic women (neither of whom, coincidently, have much interest in cycling). I purchased his postcards and brochure and he gave me permission to post his story on my site. If you enjoy it and would like to contribute to his further journeys by buying a brochure or some postcards, you can write to him at

Heinz Stucke

Around the World by Bicycle

In search of adventure and with the desire to see something of the world, I started my tour around the globe in August 1960, from my home town of Hövelhof - Germany. I was 20. 17,000 km and 20 countries later I was back home but not for long. From November, 1962, up to the present day I have been cycling and travelling non stop. If this century is called the century of progress, the century of the atom and of space exploration, one has also to say that it is the century of tourism. Because of the modern forms of transportation, countries get closer to one another every day and millions of people travel.

To travel is to learn something about one another, to meet people, to respect them and better still to make friends so that in the future we may live together in peace.

Naturally I see that not everyone can travel the way I have done for so long. Not everyone wants to. Many may ask themselves "Why does he do this?" "Why by bicycle?" "Why for so long?" The answer lies quite a few years back.

In school I was always interested in geography. I read a lot of books about other countries and about people who had travelled and had adventures. Soon I wanted to do the same. During the time I was apprenticed to a tool and die-maker I made short trips through Europe by bicycle. After finishing my apprenticeship I cycled around the Mediterranean, covering about 10,000 kms. At that time I was 18. These tours gave me some experience about how to travel and the will to see more.

By that time I did not particularly like my job and I did not see why I should spend the rest of my life doing something I did not care for very much .... just to make a living. "Is this all there is to life?", I asked, "I might as well go around the world’. Perhaps, too, I had opened my mouth a little too wide about all the things I was going to do and my friends teased me about it. So eventually I had to do something about it — if only to save face!

I came to use a bicycle on my earlier trips, partly because I felt more independent, it was the cheapest form of transportation and also because I found it to be the ideal way to see the world. It was slow enough to permit me to study each country and its people and it was fast enough to cover large distances relatively quickly. I admit that later on, most of my incomecame from the fact that I had used a bicycle for the tour.

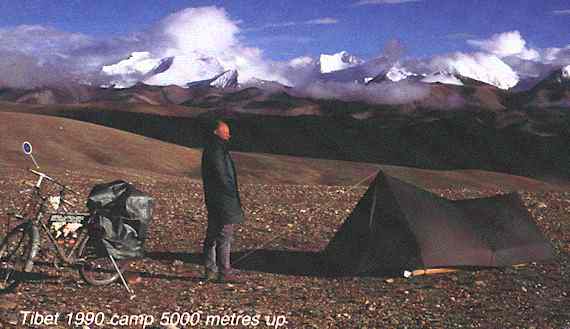

I also looked upon it as a challenge. Sometimes people ask, "Why don’t you put a little engine on your bike?" Indeed it would make it much easier for me, so why don’t I? In response to this I usually reply with another question: "Does one climb a mountain with a helicopter?" Also I found that my memory worked much better when I could associate an area or an incident with the physical hardships I had endured in each case.

Although I never intended to travel for so long, I came to the conclusion that going into an area for a short time was simply not enough. It would be very unfair to the people who lived there. You might praise or condemn a country solely on the basis of one encounter, either pleasant or unpleasant. So I decided on a minimum of two to six months per country depending on its size. I felt this period of time would permit me to get a more realistic impression of the place. But in slowing down, time just passed by and there was always another country around the corner. I was hardly ever homesick or tired of travelling, although I have to admit that sometimes I longed for domestic comforts.

The many breaks and stops and the many people who gave me a home between stretches of cycling made up for the lack of a permanent home and provided comfort.

Sometimes people pose the question, "What was the best country you visited?" I have difficulty in naming just one- So much depends on how you look at a country. What you like best depends on what you want to see.

For some it is the mountains, deserts, jungles, landscapes in general. It may be strange people or different cultures, you may like hunting, skiing, surfing, climbing, or you want adventure or a luxury vacation. I remember one time I met a group of bird watchers in the middle of the Amazon and all they wanted to do was see the birds, to add to the lists of birds they had seen and counted. I don't want to knock bird-watching, but if you asked one of those people which country he liked best, he would answer "Brazil". Why? Because he saw the most colourful birds there and that's what he likes. It's all very relative.

Because of their originally I have liked most of the countries I have seen. I never looked for anything in particular (except perhaps challenge and adventure). I try to keep my mind open, adapt to local conditions, show goodwill and hopefully receive the same of the people and put the emphasis on learning.

People often tend to assume that their way of life is the best, and some are pretty successful in imposing their way of life all over the world. The Western World for example sees to it that what is popular in the West should become popular everywhere else, although everyone knows that this Western "Way of Life" has plenty of problems environmentally and otherwise.

Tourists are notorious but often tolerated for the crazy things they do (because they have money), but they are often disliked because of that money (envy). Some are also disliked because they display bad taste in the way they behave in a foreign country. Long hair for men may be beautiful, but if it's against the good taste of a country you only offend.

I like to wear shorts, especially in the tropics, but I learned after only two days in South America that this is not generally acceptable there. It is against the image of machismo (virility) for a man to show his bare legs.

Back to the question of the "best" country. I must admit that there were some where I had better times, more excitement, and sometimes more money. But this could have been the result of luck.

Wherever I went I tried to capture the people, their lives and their environments in photographs. Besides a large collection of colour slides I have also kept a diary which describes my experiences in detail. Unfortunately, I lost some of it years ago. I had met two young Americans in Costa Rica. They were from Buffalo, N.Y., and had run out of funds after an accident with a rifle. A bullet had shattered the leg of one of them - he was wearing a cast and couldn't drive. They were eager to get home, non-stop, and therefore needed another driver. The offer to drive with them came in handy because I had wanted to see Expo '67 very much. After staying with the men in Buffalo and visiting Expo '67 in Montreal I tried to hitchhike back to Costa Rica. Not far from New York a man picked me up. After some time he stopped in front of a drugstore in a shopping centre, gave me 30 cents and said, "Would you be so kind to jump out and get me two cigars, Dutch Master Blond?" I said, "Sure". By the time I came out he had driven away with all my belongings in the car ... camera, 1,000 selected slides, passport, my diary, equipment, everything. I could not remember the car registration number although I did now that the car was a Ford Falcon. I described the man to the police, but nothing was ever found. I had to wait several weeks until I got a new passport through the German Consulate in New York and, after making it back to Costa Rica I picked up my bike and simply continued. I don't want to blame any particular country for this, but found it a little ironic that this could have happened in one of the richest countries in the world. At such a time I remembered my motto: "Every blow that does not kill me only makes me stronger".

I must admit, however, that the many friends I made in the USA were probably the best I made anywhere. The many invitations I received and the great generosity I encountered, made up by far for the unpleasant incidents. I remember the Kirbys in Anniston, Alabama. Altogether I stayed in their home seven times and I was treated like a son. Although they were not particularly rich they would give me anything that might be useful for my tour. I have met people who describe my tour as "bumming around", but most of the time the people I met expressed admiration and were willing to help. This help was not only important economically, but it was a moral support, too. It always made it possible for me to find the courage to continue.

"What do your parents say about all this?" is another question I'm frequently asked. My father did not like the idea very much at first. He thought that going to far-away places with little money would mean that my standards would fall, maybe even that I would become a criminal. Also he was opposed to the Idea of paying my way for me as he thought he might eventually be obliged to. We had a discussion (perhaps more of an argument) about this before I left and he said, "Don't expect me to pay for your tour". I said I would never want a penny and I have never had to ask him. My mother who passed away in 1966 was more on my side. Later my father accepted my travels, he died in 1989 aged 82.

By the way, what do I do about money? This problem is not one with which only I am faced. At the outset I had about $300 to spend. In those early days I spent it so very carefully that I managed on as little as 50-75 cents a day.

I was almost without money in Ethiopia, but help came along in the form of a gift of almost US$500. It was from the Government and the Emperor, Haile Selassie, whom I had the honour to meet. Later I started to write stories for a local paper in Germany and would show slides whenever and wherever I could. I made some money later on my travels by selling photographs and stories to various magazines in the countries I toured.

In South America, as in Japan, a large part of my income came from the sale of little booklets like this one. The advertisements of several sponsoring companies would sometimes not only cover the cost of printing, but would leave some profit. I would set up a little show with photographs, newspaper clippings, a world map, etc in a large city and sell the booklets. Not only did I sell a lot of them I also had conversations with many people and received many invitations.

Because my story sold so well in Japan and I spent the saved money so carefully, I could travel for several years thereafter-in the Far East, Australia, the South Pacific and Asia. Since 1978, I entrusted my story and pictures to Frank Spooner Pictures of London. All through the eighties he supplied me with US$3-5,000 per year, depending in which country I travelled in. This amount was quite sufficient, especially in the cheaper third world countries. Relieved of the sometimes heavy burden of where to find the money I could concentrate more on pure travelling. Sometimes extra spending money would come unexpectedly. Money was put in letters by friends noticeably by Douglas Waugh, Wolfgang Glunk and Rolf Möbius and much was given by Alfred Li and Flying Ball Lee in Hong Kong.

Now about my bicycle. I have met a lot of bicycle enthusiasts who asked many questions about speeds, gear ratio, the weight of equipment carried, the height of the saddle, handlebars and many other technical things that I have never thought very much about. Some will probably shake their heads in disbelief over some of the figures I give, but what I wanted was a strong, reliable cycle which needed as little maintenance and repair as possible. The cycle was given to me by a bicycle company in Germany.

It weighs about 25 kgs because it has a reinforced frame, thick spokes and solid luggage-carriers. I insisted on these things because on earlier tours I had always had trouble with broken spokes and broken carriers, etc. Imagine a broken frame in the middle of the desert! The bicycle has 26" wheels and a three-speed Torpedo hub-gear (incorporating pedal brake). I never felt that the three speeds were insufficient and I am happy with the little service the Torpedo has required. As of today I have pedalled about 385,000 kms. I haven’t kept track of how many tyres I have used. Generally a pair would last me from 2,000 to 4,000 kms depending on the road surface and on the tyre maker. Presently I get better mileage out of available brands. Only in Australia in 1973 did I have real trouble obtaining tyres to fit my bike; because sizes there were slightly different from the continental ones I was used to. When the tyres finally needed replacing and those I had ordered from Germany did not arrive, I had to use the slightly oversized Australian tyres over my worn tyres. This meant that for about 5,000 kms I rode on double tyres. In Australia too I added a second handlebar to be able to change my riding position, because of some pain that had developed in my shoulders. Most parts that move on the bike have been replaced, of course; in fact a bicycle company in Japan thoroughly overhauled my bicycle in November 1971, free of charge. While the work was being done I stayed with Mr. Hayashi, an engineer, and in the evenings when we went out, I learned about Japanese customs, drinking sake and eating sushi and sashimi. In many other matters, too, he was a great help.

With the advent of the mountain bike, which has a size and shape similar to mine, components and spares would fit my machine more easily. Out of nostalgia never considered replacement of the entire bike. By the mid-eighties what was left of the original bicycle had to stay (frame, carriers, forks etc.). Since 1988 a series of repairs, replacements and additions using mountain bike parts were done in Mr. Lee’s "Flying Ball Cycle Co." in Hong Kong. After repeated trips to China, his shop became a convenient base for repairs to my bike as well as a good place to stay.

I generally carry about 40 to 50 kg of luggage. It may be more in desert stretches when I carry food and water, and it may be less when I leave part of it with friends in case of a loop in my route. I used to send non-essentials ahead, but I have grown tired of the problems this poses and so I no longer do it. The Cycling expert will say, "How can you carry that much? It’s

impossible!" I agree, I have to walk up the steeper hills. I agree it’s slow. But I don’t want to set any records.

Now, what makes my luggage so heavy? Primarily boxes of slides and hundreds ofbooklets which I carry for sale plus, other papers like diaries, maps and anautograph book for people I meet. Then I have heavy photographic equipment and a

large tripod. Those are the heavier items which most short-time cyclists would not carry. Otherwise I have the usual things; clothing, some spare bicycle parts, sleeping bag, tools, etc. I also had a tent until it was torn apart in a storm on the grassy plains (Llanos) of Colombia. For a time, I wanted to buy another one, but I either couldn't find the ideal one or I didn't have the money at the time. Probably I didn't look hard enough. I gave away one nylon pup tent after I discovered that although it was dry outside, drops of moisture would form on the inside and because the tent was so low my sleeping bag would get wet. A larger nylon tent burned to the ground one early morning at Vienna's Camp ground because I left a candle burning and fell asleep.

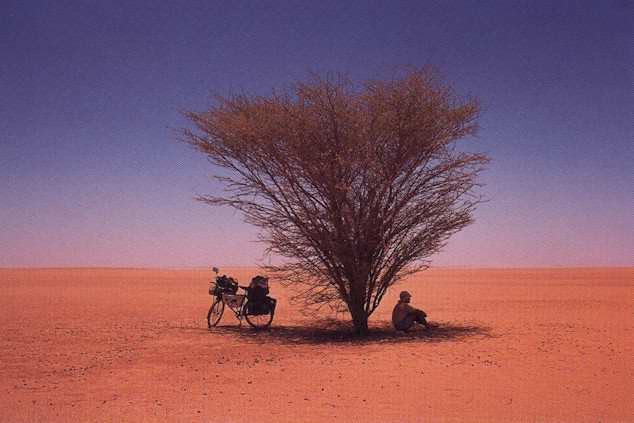

In London, in 1978 while preparing for the Sahara crossing I had chosen a new tent because of what I thought was the right combination of weight-size and price. The tent proved to be exactly what I wanted. The manufacturers of the tent were pleased that I liked it and even restarted production of an identical version when years later I needed replacement. Later on I begun to use a much larger but only slightly heavier tent made by "North Face". It easily sleeps two people and has openings and netting on both sides to allow the air to circulate more freely. That's very important in hot and humid conditions. You can dive in to escape the mosquitoes and avoid a sauna like atmosphere.

In the jungle of the Amazon where it is essential to sleep off the ground, I used a hammock almost every day. In some hotels all that is provided is a pair of hooks to support the hammock which you must bring yourself.

For a while I had cooking utensils, but I used them so rarely that I eventually discarded them. For trekking in Nepal and tours in remote Ladakh and Afghanistan I obtained new cooking utensils. At present I have a SVEA petrol stove, pots and things I need for small meals. This luggage is distributed evenly over the entire bicycle.

The sign in the centre of my cycle shows a map of the world marked with the route I have already travelled. Every other available space bears the names of places visited. I also have a sign on the back of the bike with the colours of my country and the words "pedalling around the World". This sign has caused many people to stop for a talk ... "You really pedalled around the world?" In different countries the sign had the same message, but in the language of the country. A particular question asked mainly by Americans was, "How did you cross the oceans? You didn't pedal? How can you say you pedalled around the world?" I would sometimes answer with "Well, I pedalled from port to starboard ten hours a day on the ship while I came across': or, "I put huge balloon tyres on the bike and floated across". I said anything to escape the monotony of that question. Sometimes my teasing answer led to a good conversation; "How about having a bite to eat with us?" or, "How about spending the night?" Naturally, the easy, and ideal way to meet people in a foreign country is to wait until they approach you with a question. Staying with people is as interesting as seeing the sights, but sometimes when I had to make the first move I found them hesitant and a little suspicious. So my sign helped at least in initiating the first contact. At times when surrounded by too many on lookers I covered the sign or took it away.

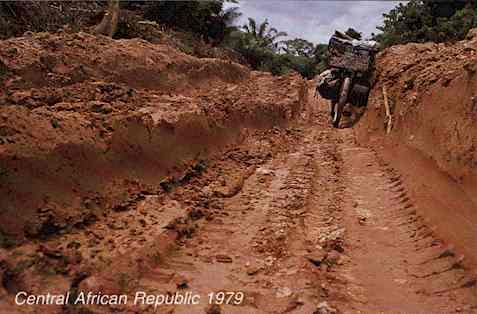

I do not have a schedule. My average daily distance is about 100 to 120 kms, but some very bad roads in Africa-Latin America and Asia sometimes slowed me down to a mere 30 to 60 kms a day. My personal record was 300 kms in 12 hours, covered in the Syrian desert with the help of strong tailwinds. I was also aided by marker posts every 5 kms, so I tried to cover a 5 kms segment every ten minutes.

Naturally one would assume that I have had my fair share of accidents-and rightly so with and without the bicycle. Besides several bad falls, caused by loose gravel or sharp curves, I was once hit by a truck in the desert of Atacama, Chile in 1965. The bicycle was damaged and the equipment was scattered over a wide area but I was only bruised.

Skip to: Heinz Stücke Page 1 | Heinz Stücke - Page 2 | Heinz Stücke - Page 3 | Heinz Stücke - Page 4 | Heinz Stücke - Page 5

Bike China Adventures

Main Page | Guided Tours

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, 1998-2005. All rights reserved.