China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

Stephen Lord

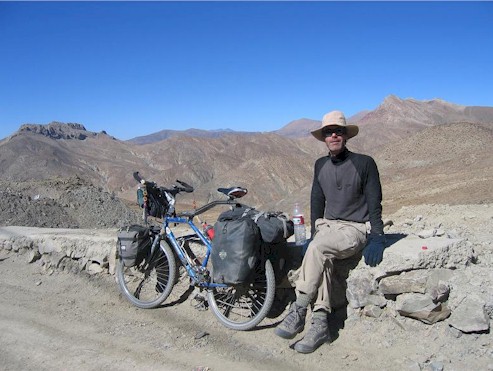

Biking Solo from Lhasa to Kathmandu

Reflections from a Cycling Trip of a Lifetime

Copyright © Stephen Lord, 2005

Kathmandu, November 2005

I am now in the fleshpots of Kathmandu nursing a swollen knee that had made the last weekís riding very painful. Wearing cheap hippy rags I bought to tide me over, all my clothing is in the wash today, the trousers having been unwashed for the entire monthís riding, and most of the rest going for a week or more without so much as a rinse. It will take a long time for all my thoughts and feelings about Tibet to settle down and I cannot expect to reach any sort of conclusion about it, except that it was a very special trip indeed.

It was a hard ride, very hard in fact. All the bikers around me were hit by fierce headwinds on many days but I was spared for all but one 20km section that is so certain to have headwinds that itís marked on the map. I was even so rash as to tell the French couple I was riding with that if they stuck with me, they wouldnít have to worry about headwinds on the last and notorious pass, which is exposed, snowy and icy. Indeed we didnít; we had a tailwind that day. For the last week, the temperature never rose above freezing and fell to around Ė15C at night. Our hands would become colder and colder until around 11am when strong sunlight would finally thaw them. My hands were the weak point in my armour against the cold, as I only had windproof fleece gloves and the weather called for ski gloves. It was a source of some serious concern while I was camping as I could not wash up after breakfast without great risk and pain to my hands. I kept thinking of a famous short story by Jack London set in the Yukon, called ĎTo light a fireí, about a trapper whose hands freeze while he tries unsuccessfully to light a fire, each match burning out or falling in the snow before the fire is lit. He doesnít make it. While I was pretty warm in my tent, camping was a matter of survival and my thoughts never rose to the higher, transcendental plane that one fancifully hopes it might in places like Tibet. Perhaps that is the insight: Just keep your eye on the ball, matey, itís all about survival. The last day I camped, my washcloth froze in less than 5 minutes and my glove stuck to the pot in the morning. I could not afford to be in the least thoughtless or forgetful. Essentials that must not freeze must be inside the tent, which never fell below freezing point; goodies such as my honey supply slept with me in the sleeping bag.

Camping for bikers means looking for a spot near water, out of sight from the road, and sheltered from the wind. Motorists would never look for such places, but bikers do and they pick the same spots. In central Tibet itís almost impossible to be unnoticed or entirely alone; there are shepherds and their flocks at all altitudes, even, it appeared, where there is no grass for the animals.

Once my tent was up, I would lie still for half an hour to rest, and then get on with fetching water and making dinner. It was impossible to find good food for camping in Tibet, just instant noodles. To vary the diet, we discovered that instant noodles can be eaten uncooked too, and taste quite different. A refreshing change. I found some short grain rice and tried cooking that, but at altitude you need a pressure cooker for rice; porridge came out well, though. I had a modest supply of cheese, the fats being useful in that climate, but it soon ran out and I found that edible cheese cannot easily be found in Tibet, or not at that time of the year. We had been shown a fine collection of cheese in a restaurant in Lhasa the night before leaving. With other bikers from Switzerland, Austria and Germany we were admiring the cheese the Nepali restaurant owner had brought with him from Kathmandu and all bought some, but it was the last good cheese we were to see. Yak butter is pervasive in Tibet and it smells like cheese but is quite different. I am unusual in actually liking yak butter tea, but as someone from the BBC said (in Michael Palinís Himalaya book), if only they called it soup and not tea, we wouldnít have a problem with it.

The ride itself was tough except when on paved roads, but as I often say to people Iím biking with, and I hope my book (Adventure Cycling Handbook) makes clear, a rideís never just about the riding, itís about the things you see and experience along the way. I would never have met the people I met, and certainly not the dogs, had I been in a Land Cruiser. In fact the Land Cruisers were the real hounds from hell, driving at insane speeds without regard for man nor beast and churning up incredible dust, while destroying the roads. The old unpaved roads were fine for low levels of light traffic, but cannot cope with two-ton beasts driving at 40 mph. Thatís why Iím happy to see the Friendship Highway paved over. The locals found it dangerous in many areas and it has been destroyed by these automotive tanks. I sometimes followed Tibetan horse and carts and light vehicles in taking parallel tracks next to the road. These appear whenever the road has become too washboarded by the weight and speed of traffic. When the road is paved, foreigners will find itís cheaper to take the bus than hire a Land Cruiser, and hopefully the hounds from hell will be out of business.

Those other hounds, though, that was an interesting thing. After sheep and goats, yaks and other bovines and then humans, dogs are probably the fourth most common animals in Tibet. Every night that I stayed in a village the nightly lullaby of barking lasted for hours. The exhausted dogs would then sleep all day when not picking amongst the rubbish. These dogs are not pets but scavengers that live outside all day and night. They ignore bicycles and humans generally, but live among them. I had only two encounters with dogs and they were brief; thankfully I never met nor saw a Tibetan mastiff. A trained or abused dog is the one to worry about, the rest deserve only pity. They do a poor job of sorting out the rubbish, though. If only they could be trained to eat plastic theyíd be a lot more use to humans. Unlike yaks, dogs provide no fuel, transport , food or clothing, and the ones I saw were pretty lousy sheepdogs too. Tibetans tolerate them, though, perhaps, as people say, because they are Buddhists and think the dogs may be their late uncles. I doubt that, as all Tibetans, including monks, are keen carnivores but wherever Chinese predominate, the dogs are dealt with

I saw plenty of monasteries, so much so that I skipped a few in the end. I saw thousands of Buddhas and have hundreds of photos, though none as good as that first Maitreya Buddha I saw at Sera monastery (sent in my earlier email). Many of the big monasteries now charge admission, and as I said before, itís changed the relationship, inevitably, to something closer to tourism and fund-raising. The kinds of encounters my Tibet guidebook writer Kym McConnell had are far less likely nowadays and I had only one such experience when I visited my first monastery after leaving Lhasa, some 20km down the road. I was the only visitor, there was no entry charge, and the Abbot showed me round the monastery. Endless cups of yak butter tea followed as I listened to their prayers in that distinctive but satisfying drone, then the invited me to lunch. It was still early days for me in Tibet, the filth and hygiene standards shocked me and I expected to fall seriously ill within hours after a very poor quality lunch with them, but I survived and have a superb photo of all the monks sitting together at lunch in a ĎLast Supperí pose with the Abbot holding their white cat Shimi on his lap. I shall try to send some small photos when I can get a fast connection, including that one. It was then that I remembered I still had that contraband in my bag, the photo of the Dalai Lama. I took the Abbot back into the chapel for a last look and showed him the book Ė he blessed himself and the book and was thrilled to see it. Later I found another Dalai Lama picture in the book while it was being passed round in a guesthouse that regularly had PLA (army) and police visitors in a small village near Everest Base Camp. Thankfully only one older Tibetan recognized the quite small image of His Holiness and though he too blessed himself and the book by holding it above his head and touching his forehead with it, nobody noticed that either. I managed to give that photo away the next morning as we left the village, to two ancients who had given us some tsampa (roast ground barley) to eat.

The greatest experience of all was simply to be among the Tibetans and see their way of life up close. It is best done on a bicycle as so much of life takes place outdoors, by the roadside and most of the country is involved in farming. The hotel manager who sat with me at breakfast this morning told me he finds Tibetans to be naturally lazy, but no-one who farms can ever be lazy. They simply donít want to change for our convenience, and whatever the faults of their way of living, they have survived in that climate and that barren land for many centuries and donít want our reforms or improvements. On our last day, we stayed in a private house near Milarepaís Cave (Milarepa being the 14th Century monk now regarded as a saint). It was a wonderful evening, the more so for it being just a house not accustomed to taking in guests but happy to do so (always for money, of course). The house the usual low-ceilinged, earthen-floored house made of mud bricks with doorways as low as 5í high, the food just vegetables on rice with a few bits of yak meat. Cows kept indoors at night and the Tibetan TV channel for entertainment as well as radio. TVís a bit of a bore as it is across all of Asia, but itís come on a long way and is not as bad as, say, North Korea. The Chinese president was shown visiting North Korea and watched one of Kim Lu-Niís dance spectaculars seemingly involving half the nation. From his face, Chinese president Hu Jintao could not believe what he was seeing, for it was straight out of Stalinís era in the 1950s, a sort of Lost World of communism. There are reasons to believe the current Chinese administration is liberalizing, but much of it I saw in Hu Jintaoís face; the look of embarrassment when confronted with the legacy of communism by his demented distant North Korean political relative. I think Hu Jintao found the Vietnamese heíd met the previous week considerably more enlightened. It was clear from listening to the radio and watching TV that many things can be aired nowadays in China that were unthinkable only a while ago, yet the old man in that modest house sat with a print of Chairman Mao behind him on the wall, next to the Panchen Lama (the tenth, the old one whom the Chinese bullied to death). Our host didnít need the progress that is coming, but I have to credit the Chinese with making those huge investments in electric power, television, roads and schools.

Much of Tibetan culture is robust and flourishing. I was pleased to see that despite the inroads Chinese architecture has made in the bigger towns Ė and itís all appalling stuff Ė Tibetan homes are still the norm in the countryside and the old skills have not been abandoned. Wood framed windows (thankfully the man from Everest Double Glazing hasnít called on Tibet yet, having trashed British suburbia), square whitewashed buildings with courtyards for livestock, neat piles of yak dung ready for winter all make a very pleasing picture. In towns the homes overlap on different levels, much like old Santa Fe in New Mexico, giving a very organic look and feeling. Even in towns, each home has a courtyard and small stable or barn for the animals, and the narrow streets have no traffic whatsoever. Once you are used to the smells, which are not too bad, itís a lovely scene and there are plenty of new homes going up. A lot of farmers must be doing well, too, as many of the new homes, though in the traditional style, have some luxury features such as the beautiful painted Tibetan woodwork under the eaves and above windows, doors and gates.

I spent the last week riding with a French couple I met, two really delightful people, Marc and Annick, whom I shall be seeing this evening for dinner. Marc was a super-athlete of 31 years, Annick was pretty strong too but inevitably far behind him. Her courage and determination was admirable and needed. I saw her fall off the bike at slow speeds perhaps five times, going through streams or downhill. I could easily catch Marc going downhill as my bike has full suspension and could thunder through anything, while Marc had to pick his path more carefully, but uphill, he was in superb form and had a really light bike. One day Annick and I hitched a lift over the worst pass. My knee was in bad shape and Marc telephoned to say that though he had climbed the pass, the headwinds at the top forced him to hitch the rest of the way. Itís fairly easy to hitch in Tibet, that is to say the success rate is pretty high as Tibetans know foreigners will pay for a ride. We got an empty three-wheel truck driven by a cheerful young Chinese.

Later we rode into the Everest Base Camp area. We rode over the big (5200m) pass that has been newly graded and rerouted at easier gradients, but we couldnít get out two days later without transport. We made it halfway to Everest and stayed at a guesthouse that doubled as the village pub and looked like a scene painted by a Tibetan Hogarth on Saturday night. Drunken guests stayed over, sleeping in the bar. Marc tried to rouse them for breakfast Ė I was always amazed at his optimism in thinking he could get them to agree to provide breakfast at 8, or any other hour. Tibetans in the countryside donít use watches and get up with the sun. Clocks are on Beijing time, so 8am is quite dark in November, and in the villages, the electricity isnít turned on in the morning so getting up in the dark is simply not done, but Marc rightly wanted to avoid the likelihood of headwinds late in the day.

We set out early on a beautiful crisp frozen morning for Everest Base Camp, 50km away but we planned a round trip and were not carrying our bags. We made barely 10km/h over a road so rutted it was painful even on my plush bike, but agony on theirs. Marc and I stopped to wait for Annick Ė he had an irritating habit, I thought, of getting too far ahead of her Ė and he told me to go on ahead and he would go back for Annick. In that cold, without any backup gear and on my own, I knew the plan for Everest Base Camp was up and went back with him. We found Annick by the side of the ride having some sort of seizure Ė they later told me it was what the French call a crise tetanique. Stress or exhaustion had led to this, Annick sitting on the ground frozen rigid, her hands shaking and unable to move, shivering. Marc, a trained mountain guide and ski instructor, lay her down, put a plastic bag over a face, the last thing I would have done but after a few minutes she slowly came around. Weíd had to stop before a couple of times to take her shoes off and rub her hands and feet to warm them up but this was the limit of our trip; Everest can wait.

Iím still astonished by her courage no tears or drama, a real determination to stay the course and never a harsh word spoken between them. Iím still a bit surprised by all of us, the Frenchies and I and the other bikers I met and those I keep in touch with, for doing rides like this. These trips are no ordinary holidays. They have meaning and importance regardless of whether they are pleasant or easy or not. They allow us to see other people, and ourselves, in ways we could not had we opted for the passivity of sitting in a Land Cruiser. ďWe were sealed insideĒ said one Land Cruiser passenger to me of his experience, referring to the need to keep the windows closed to keep the dust out. It was we cyclists who absorbed your dust; itís still in my throat and Iíve been coughing and croaking for weeks.

Bikers headed for Kathmandu talk of it as the paradise at the end of the road, but like anything so longed for, it can be a disappointment. Certainly there is immense culture shock, as is common when visiting any of the South Asian countries, but especially when coming from a place like Tibet, so sparsely populated, so barren and sometimes colourless and quiet. The riot of sounds, that first Tata horn when you enter Nepal, the warm smell of rotting garbage (it freezes before it rots in Tibet) that reminds you of past trips and all the great things to come, can soon repel and make you miss the simple, elemental feelings of Tibet. It took two showers to get the smell of yak butter out of my hair. A hard smell to get used to, I shall miss it.

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.