China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

Pete Richards

"Solitary in Tibet"

Copyright © Pete Richards, 1993

My journal entry describes Sept. 14,1986, as "one those memorable days I shall cherish forever." I mountain-biked to the to 16,000 toot Khamba La pass overlooking Yamdrok Tso, sacred Turquoise Lake of Tibet, and wrote: "The climb starts fast soon after leaving the nameless village at 12,000 feet. The road is not terribly steep and, though not paved, in fairly good condition nowhere as bad as the one I had been training on above Santa Fe. There is just a minor altitude problem. The first couple of hours went fairly well although my legs were aching. But by three hours I was in the very lowest gear, biking 15 and resting 15 minutes, eating up all my biscuits. Then, a kilometer or so from the top I saw the prayer flags marking the summit. This gave me a real spark though I would hardly say I was sprinting at the finish.

"...joy and elation. even now writing about it a day later I got choked up. Probably only someone who 'uses his body' understands what it means to have put out 110% to achieve such a goal, and to have done it here, in magnificent Tibet, produces a high beyond description."

That day was during my second trip to Tibet. The year before I had made a more conventional, tourist-type visit. Like many of my generation, impressed by Hilton's Lost Horizon, I had dreamed of seeing the roof of the world" and searching for Shangri-La, Lhasa is Tibet's major city, had just been completely opened to tourists and I learned that future travel could be done independently much cheaper. After having been driven up the same pass by Land Cruiser and seen the lake below and the surrounding Himalayas, I vowed to return by mountain bike.

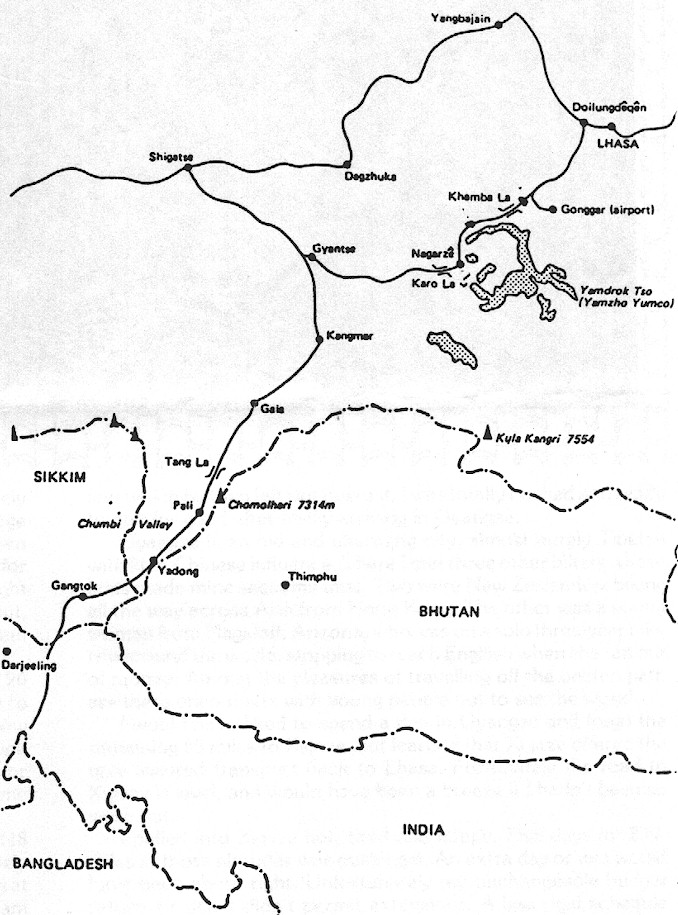

One year later I was back in Lhasa prepared to bicycle the, 210 miles to Xigaze, Tibet's second largest city, which would take me over Khamba La and an even higher 17,000 foot pass along the way. This may have seemed foolhardy for a 51-year old family man employed as a research physicist in Albuquerque. But, being a regular runner of the Pikes Peak race and having run the 72 miles around Lake Tahoe, it was not so far from my normal level of insanity.

Two important things, learned on the first visit, made the venture seem possible. First, Tibetans are very hospitable, and second, pictures of the Dali Lama are more valuable than money. I had bought a small picture on the street the year before returned with a large supply of enlargements made from a photocopy. My assessment that the photos would assure ample food and lodging in the small villages was, if anything, an underestimate. At one point I revealed that I had many pictures, which was about as wise as flashing a large roll of money on the streets of an American city. Not that I was harmed or had any stolen, but the large crowd of beggars who gathered refused to comprehend that the pictures were for those who had helped me in some way, not for the whole population.

Communication was with a combination of broken Chinese and sign language. The former, of which I had learned enough to survive, is a second language to the Tibetans, not spoken by many of the villagers. Nonetheless, it is not difficult to make known that you want food and a place for your sleeping bag, especially if the request is accompanied by a smile and a Dali Lama picture.

I regularly biked up to 12,000 feet outside Santa Fe to train as best I could. But this is only "sea level" for Tibet, roughly corresponding to the starting elevation of Lhasa, the lowest point on route. There is no adequate way to prepare for the major unknown of coping at 17,000 feet. Even a Pikes Peak runner like myself could get altitude sickness and should get down the mountain at the first sign of real trouble. Fortunately, descending a dirt road or mountain bike is quicker and easier than getting down from Everest.

My primary concern, though, was less with my own high altitude survival than with the bike's survival from Albuquerque to Lhasa. I opted for a canvas bike bag rather than a bulky box, and it proved to be equal to the challenge of international travel. The route included an overnight stop in Hong Kong where I secured a visa to China, now also good for Tibet. Such paper work is done much more readily in Hong Kong than in the U.S, One can also fly directly to Beijing or Shanghai and obtain a visa on the spot.

All air travel to Lhasa originates from the Chinese city of Chengdu. Securing advance reservations for domestic flights of CAAC, the airline of the Peoples Republic of China, is about as easy as finding Shangri-La. The mad dashes through airports with the bike bag and being told that my "confirmed"" reservations were invalid all seem pretty funny now, and are a story in themselves. They weren't so funny at the time. This difficulty, as well as that of getting hotel rooms in the main cities of China, is not faced by the less-adventurous traveller in an organized group, and is something the independent soul has to be aware of.

Lhasa itself is such a delightful place that a certain amount of inertia has to be overcome to leave it. The Jokhang Temple and surrounding square is the center of activity. One can spend endless hours fascinated with the throngs of devout pilgrims and irresistible smiles of the Tibetans. Lhasa was even better this time because! stayed at the Snowland Hotel just off the square instead of the pricey new tourist hotel where I was the year before. An accurate statement about the Snowland from the guidebook, ("Tibet, a Travel Survival Kit", by M. Buckley and R. Strauss, Lonely Planet Publications, Berkeley, Calif., 1986) is; "It's impossible not to like the Tibetan women who run the place with laughter and waterfights". This more than makes up for the lack of such amenities as running water and indoor toilets.

After a few days of acclimating I remembered the main purpose of the trip and pedaled away from the charms of Lhasa. The five-day trip would take me over the 16,000 foot Khamba La 60 miles from Lhasa, down to Yarndrok Tso at 14,500 feet, to the village of Nagarze at the end of the lake 82 miles from the summit, up and over Karo La pass at 17,000 feet and 16 miles out of Nagarze, 47 miles down to the town of Gyangze at 13,000 feet, and the remaining 55 level miles to Xigaze. One of the more adventurous features of travel in Tibet is that there are no detailed maps, so I didn't know for sure where I might find villages. The year before I had spotted the first-night's stop 35 miles out of Lhasa just before the climb starts up Khamba La, but after that it was anyone's guess. Presumably these villages have names, but there aren't exactly big signs announcing them. Even if there were, they of course would be in Chinese characters and/or the Tibetan alphabet--not too helpful.

The first 30 miles were on the same paved road that leads to the airport. A tailwind and the company of two Chinese teenagers on their one-speed bikes made it a fast, easy ride. Non-Orientals are not uncommon in downtown Lhasa; so one can bike around without being mobbed, But once in the country it's a different story. Every rest stop, even in a desolate area, brings a crowd of curious children and adults. My first such encounter, repeated frequently during the days ahead, came shortly after leaving the paved road and my biking companions. All my items had to be examined, camera lens looked through, and, most of all, the strange bike thoroughly gone over. All would dearly have liked to ride it, but I drew the line there, especially since none had ever ridden one with gears. Body hair, scarce among Orientals, is also an item of great interest and often gets tugged. I could always get a laugh by showing how comparatively little there was on top of my head.

The first night's lodging was authentic Tibetan farm life with chickens running around the dirt floors and jumping up on the dinner table. The meal consisted of barley which is the staple of the Tibetan diet and all one gets in the country aside from the ever present yak-butter tea. This, as the name implies, is tea into which yak butter, the more rancid the better, is dissolved. It is the national drink which is served continuously. Many have described it as undrinkable, but I rather like the stuff. The ultimate Tibetan delicacy is hot breakfast cereal of barley flour mixed in the tea and eaten with fingers in place of chopsticks. Although sanitary practices in China and Tibet are best not discussed while eating, my, stomach survived. This may have been pure luck, but I did take the precautions of peeling all fruit, eating only well-cooked vegetables and Katadyne-filtering all water that I had not seen boiling.

After the dinner of barley soup, barley beer and tea, I was given a soft comfortable place to put my sleeping bag, there to dream of the big day ahead. That of course was the ascent of Khamba La described at the beginning. The journal's narrative continues with my elation at the top: "I yelled, I screamed I cried. Only someone made of stone would do less. Close by was an older Tibetan woman who witnessed all this. Instead of thinking ma a lunatic, she understood perfectly. Mountains are part of her religion too She had come to make offerings at the prayer flags at the summit. She gave me some bread and examined my bike. I gave her some water and a Dali Lama picture. She then let me take her picture, something very rare for a Tibetan woman. Our common experience brought about a strong rapport.

"Although I would have liked to savor the view and our companionship much longer, it started sprinkling which forced a quick 1,500 foot descent to the lakeshore. It was so beautiful and its it water so clear that if I had a tent I would have stopped immediately for the night. Instead I continued a dozen or 50 miles to a village where I was happy to call it quits. There was the usual crowd when I stopped, and shortly arrangements were made to put me up for the night. Later I was quite ready for bed which, similar to the night before was outside but protected by an overhang. Stars came out, the first time I had seen them because of overcast. Watching them in the clear night sky was the perfect end to a perfect day.

The following day required rest, and I only biked less than 20 miles to Nagarze at the end of the lake, stopping frequently to admire views of the distant Himalayas. Although there are now more donkey carts than motor vehicles, Nagarze is a major truck stopover with a hotel and restaurant where I had a single room for 80 cents and ate something other than barley for the first time since leaving Lhasa.

From there I had only two more days to get to Xigaze, still 118 miles and a 17,000 foot pass away. The Karo La pass immediately outside of Nargaze is much easier than Khama La. I was starting at 14,000 feet and now had the confidence. The road follows a stream between 23,000 foot peaks. Nothing could match the excitement of the first summit, but I was only slightly more in control of my emotions at the top. And this time I had more people to share them with A truckload of Tibetans pulled up followed by a Land Cruiser with a couple of German tourists. The Tibetans cheered with joy upon reaching the top (given the condition of their vehicle, this was probably warranted). After making offerings at the prayer flags, they made offerings to me in the form of hard boiled eggs and a bottle of beer. No beer has ever tasted so good, and I couldn't have cared less about its possible effects at 17,000 feet. From now on it was to be all downhill.

But alas it wasn't. After the initial drop to 13,000 feet, there were many ups and downs, including one climb of a few hundred feet which by then felt like Everest. I was totally bushed and ready to quit for good after finally arriving in Gyangze.

Gyangze is an old and charming city, almost purely Tibetan with little Chinese influence, There I met three other bikers whose feats made mine seem minimal. Two were New Zealanders biking all the way across Asia from Hong Kong. The other was a young woman from Flagstaff, Arizona, who was on a solo three-year bike trip around the world, stopping to teach English when she ran out of money. Among the pleasures of travelling off the beaten path are these encounters with young people out to see the world.

I would have liked to spend a day in Gyangze and forgo the remaining 55 miles to Xigaze, but learned that Xigaze offered the only assured transport back to Lhasa, Fortunately the road to Xigaze is level, and would have been a breeze if I hadn't been so worn out.

I pulled into Xigaze hot, tired and happy. Five days for 210 miles at those altitudes was pushing it. An extra day or two would have been about right. Unfortunately, my unchangeable budget return air ticket didn't permit extensions. A less rigid schedule next time may be worth the extra cost.

The bike rode on top of the bus while I sat next to the driver for the ten-hour trip back to Lhasa. I felt a secret pleasure every time the engine wheezed to a halt on the passes, and we had to wait for it to cool off. The old bus was having at least as much trouble as the old man.

A hero's welcome and a room to myself with three beds for the price of one was waiting at the Snowland. The next day I said my goodbyes. The smilingest and liveliest of all the smiling and lively girls at the hotel engaged me in a water fight at the well, which I took as the greatest compliment. I told here I would be back next year. Not to return to Tibet is unthinkable.

(Footnote: I did return and rode the Lhasa Kathmandu route.)

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.