China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like to share here?

Contact us for details.

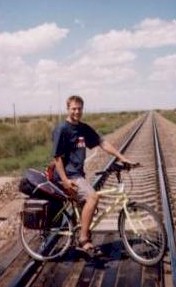

"On Tracks and Trucks"

A broken bike (and an encounter with quicksand) gives Jonathan a break from biking in northenmost China

By Jonathan Litton

Copyright © Jonathan Litton, 2006

Eighteen Station

I am writing from Shi Ba Zhan, a town whose name translates as Eighteen Station. It does indeed have a station, though locals assured me that it was not therefore called Eighteen Station Station. In the last couple of days I passed through Twenty-Three Station, Twenty-Two Station and a whole string of similarly unimaginatively named settlements in the middle of nowhere. The railway may have made it to Eighteen, but the likes of Twenty-Three and Twenty-Two are isolated outposts in the taiga - the never-ending forest that spread over the border into Russia and continued for thousands of kilometers. Indeed, I was tracking the Sino-Russo boundary as part of a cycling mission that deliberately took me through some peculiar places. The sequence of stations certainly qualified; nary a normal soul was found among the inhabitants.

The Arctic Village

My journey to Eighteen didn't go as expected, but was much more interesting than once would anticipate from a 400km stretch of track through the taiga. Let's go back to Mohe, the last semi-civilised place that I encountered. Mohe is the gateway to the 'Arctic Village' - China's northernmost settlement. For this reason alone it registers a small blip on the radar-screens of devotees of off-the-beaten-track travelling. Lonely Planet gives the place a mention; all but the hardiest of travellers give it a miss. In the winter I had scored a hit, arriving at a time when the temperature was at the one and only point where Fahrenheit and Celsius fans alike quote the same figure: minus-forty.

This time round I met a Taiwanese tour group, bumped into the same taxi driver that had served me in the winter, and pored over some maps with a former cyclist. He was from southern China and had done over 10,000 kilometres taking in the deserts of Xinjiang, the mountains of Tibet, the huge lake of Qinghai and the stone forests of Yunnan. He had even done a lot of the border routes in the northeast that I would be tackling later, and gave me a few tips on where soldiers were. I had guessed as much from the geography - the few stretches of land border appeared to be heavily fortified.

As I was pedaling northbound, I caught the scent of an Aussie who had done some of the same route as me. In these one-shop villages, if he passed through, the chances are that he met the shopkeeper (you buy supplies whenever you can in these parts) and so in a couple of places I was told about him. I don't know whether he was years, months or days ahead of me. It just goes to show that there are other like-minded folk out there, and I think I've got a lot more cycling in me. I have found what I really enjoy and this little mission will hopefully be the test run for something bigger and better!

Braking for the Black Dragon

The Arctic Village sits on the bank of the delightfully named Black Dragon River, the eighth longest river in the world and the border between China and Siberia. It takes some getting to. Considering that ten days earlier I had followed the Argun River, one of the Black Dragon's tributaries, and that I had climbed a lot since, I knew that on average I would be going down, down, down. Well, there were a lot of ups too, as had to pass some mountains first, and ten days of climbing were repaid in the final 10-15km; one of the most awesome descents I've ever done. It isn't the kind of place you want brake failure, which is what happened to little old me! I tried to keep my speed in check by slaloming down the road, by using my feet to brake on the turns, by hurtling through the sand at the side of the road, and by general blind luck. In places though I was a runaway train, and just had to hold on tight, praying that there were no bulldozers lurking round corners. There weren't, but there were plenty of rocky streams to ford, and I hit on at an incalculable rate, experiencing some serious air-time for my efforts.

I saw the other side of the valley and knew I must be homing in on the mighty Black Dragon. As I was straining to see the water, I noticed that my road would take a sharp turn to the left in a second. Too sharp for me, but fortunately a track continued straight on. Unfortunately it was the entrance to a military compound and had armed guards either side. Damn! I got through inches of shoe leather and skidded to a halt about ten metres from the soldiers. They were of the beefeater-esque mustn't-move-a-muscle training and were stationed to face each other, their steely gazes forming a laser beam designed to intercept any miscreants daring to break their line of sight. On this occasion their training failed them and they turned to see a "foreign devil" on a bike smile and disappear pretty quickly. I hope they were severely reprimanded for their breach of discipline!

Mohe in midwinter

At a sensible pace I continued to the village itself and befriended the boatmen who ran a passenger service from this isolated outpost to a big river town 800km downstream. They gave me a nice little pin badge which announces something like "Mohe northness tourism", before pointing laughingly at a soviet police boat which was patrolling the river. Their hilarity only increased when they heard that I had cycled from Mongolia and was bound for North Korea, and they invited me on board for some beer and noodles before taking the boat out for a bit of a spin. Whether or not you can be charged with being drunk in charge of a boat, I know not, but apart from the soviet soldiers - who we steered well clear of - the opportunities for a prang were few and far between, thank goodness. Opportunities for pranks, however, were decidedly abundant: the crew play-fought and jokingly inserted freshly-caught fish into each other's noodles. It would seem I had found some folk with an even more childish sense of humour than myself.

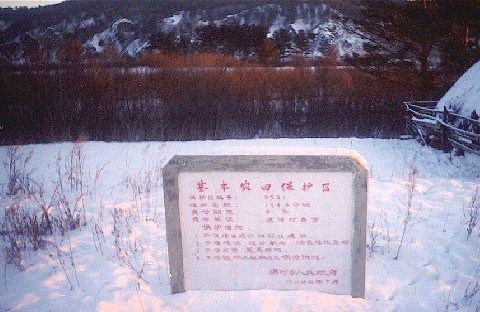

Northern Exposure

Once the mayhem was over, I submitted myself to the complete northernmost experience. This consisted of posing heroically by a rock engraved with red Chinese characters, standing by a rock and having a photo, peering at the northernmost house and squinting at Siberia (the forest on both banks, of course, looks exactly the same). Other than the exceedingly rare northern lights, there isn't really that much for tourists who make the monumental trek up here to do. I pity the Taiwanese who came by plane, train and minibus - that's a lot of motion sickness for a run-of-the-mill Chinese village. And there's a sting in the tail for those who do come - the characters on the rock that I imagined to be oh-so impressive were illegible to every Chinaman I met.

However, it is the other type of characters that the trip is all about. That's the beauty of travelling by bike: you get a lot of interactions and meet people that you wouldn't otherwise get to meet. After saluting Siberia I met someone who was really dumb, in the medical sense. I've never met someone that couldn't speak before, and I was surprised the villagers didn't seem to have a system of sign language with him and that he was wearing a police uniform. But then cynical old me shouldn't be surprised any more; I can just imagine the Chinese trumpeting a huge success story about how they integrate all members of society, the evidence being his role in a vital service. But the uniform and pay packet do not equal integration, and sticking him in a village at the end of the (Chinese) universe and basically ignoring him isn't so noble in my books. (Or he could have just been wearing a fake uniform - I acquired one about 1,000km down the road. But you really don't want to get me started on forgeries – I could rant about fakes ad infinitum.)

After several days of serious mountain biking I was pretty tired, so booked myself into an inn rather early. I halved the price from 20 yuan to 10, paid up, and turned in. I was therefore not too amused when my "friend" the driver (the guy from my winter trip that I had bumped into in Mohe) came knocking on the door at an unholy hour, shouting "Nasdun, Nasdun" which I presume meant "Jonathan, Jonathan". I got rid of him, returned to sleep, and awoke in the morning with the intention of making an early start. As I was exiting though, the hotel owner (a tiny old woman) asked for my money, claiming I hadn't paid. I stopped for a moment, thinking how to say "I paid yesterday," and as I was so doing the driver's fat face appearing round the door accompanied by an equally fat wad of cash.

"Renminbi, renminbi!" he bellowed. ("People's money, people's money!" - one way of saying the Chinese currency). I proceeded to present my case in broken Chinese. She stopped to think. Despite the fact that she produced a 10 yuan note from a separate pocket from the rest of her money, she wasn't convinced that I had paid her. I wasn't convinced of her argument that went: "we-ell , I had 38 yuan yesterday, and now I have, erm, I can't count.... but the amount includes a 50 yuan note, so my argument clearly breaks down and I am either a forgetful old hag or an extremely shrewd and skilled actress, and either way I am putting the foreigner in a lose-lose situation, and will extort his money." It was two against one; Chinaman and Chinawoman against foreign devil. I didn't stand a chance, and duly coughed up.

The borderland coffers are rolling in my money - my "friend" the driver was probably so friendly towards me because he caught me as a first time solo traveller in China when my Chinese, bargaining skills and savvy were non-existent. That I had handsomely overpaid him, I had no doubt. And on my current trip I was turfed out of a cheap bed in Mohe (the last stop before the Arctic Village) by the authorities who led me to a "safer" (read "expensive") hotel. This last point is annoying, but bearable, as I knew such rules existed before I came to China. It's their country, and in choosing to visit I had chosen to accept the law of the land; if I couldn't put up with it, I shouldn't have been there. What made me irate on this occasion was the fact that I was happily talking away to my cycling friend, when along came this brute representing the authorities, speaking unintelligible Chinese (slurred, accented, impossibly fast, etc) who forcibly moved me to a new hotel there and then. I didn't check into the hotel in his presence, which annoyed him (and therefore afforded me a little bit of gloating), but I lost out on the rare opportunity of sharing cycling stories. Anyway, that made it three times in one place I had been stung: I had been overcharged by the driver, had forked out for approved hotel, and had paid the thieving little old woman twice for one night). I was not too amused.

Exit Strategy

However, of greater concern than money was devising an exit strategy. Somehow I would have to climb out of the bottomless pit I had descended into. Unless... Well, there was a small road beside the river marked on my map, and there was another riverside village about 50km downstream. The line on the map indicated that the road only made the trip for about 10km. but I posited the existence of a pathway between the two. The game of inventing theoretical roads had worked in the past, as the maps of these parts are sketchy at best. All was well and good for 20km or so until I turned a corner to find...a turning circle. Dead end. There was no way through the impenetrably dense forest, so I had to backtrack.

However, I had seen a lot of trucks and tractors on this river road; more than I deemed necessary to serve the three farms that constituted the settlement at the end of the track. So I followed them through an unlikely side-track up the mountain, hoping that it would connect with something else. Which it did, in fact, after an untold amount of climbing followed by roller-coaster descents. The trucks were serving a quarry of sorts, where men chipped the rocks by hand. Well, the hands wielded axes, but still, it looked pretty primitive. Then 30km of nothingness, although a lone betractored yokel confirmed that this track linked with my road east.

There was an absolute ghost town at the crossroads, consisting of about 50 derelict houses. The place was littered with broken glass and had wood chippings everywhere. It was a little eerie. I was going to stop and take photos except it transpired that some people actually lived there, and had the type of body language that said "move on else I will fetch my rifle and send you to kingdom come". So move on I did, passing under a barrier and onto my road, marked here by "688". That's a lot of kilometres to do on a sandy forest track, wherever the zero point lies. Ah well, nothing for it but to push on, which I did for hours and hours, with continuous rain, mosquitoes and hills. I managed to propel bike through 60k of this mud, which I was impressed with, considering I very nearly camped out after 23km. In all this time I only saw one car.

In the dead of night a battalion of trucks rattled past, their headlights creating a huge silhouette of my bike on the tent lining, which was weird. I thought a little about tigers, and whether or not they could climb trees, but considered statistics to be a far better defense than tree-climbing. Two days before I left for China I had caught a documentary on the Amur tiger, which replayed a single killing of a sheep about 18 times, which suggested they were kind of low on footage, which in turn suggested human-tiger interactions were something of a rarity. Indeed, it is estimated that as few as 20 of the beasts may be in China at any one time, the rest opting to terrorise the North Koreans or Siberians. So, "Oi! Big cat! Go eat Bell's theorem, not me!"

The next day I gave further abuse to my bike largely owing to the "runaway train" effect on the downhills, which inevitably led to the multiplicity of problems. A good example of this would be an athlete who alters his running style due to an ankle injury, then ends up putting untold stress on his shoulders, only to break down with chronic back injuries. Of course, it is best to stop the problem at source, but try telling the runner that the night before the big race! The net result was that my bike was in very bad shape, but the afternoon at least brought me a reference point (a tributary of the Black Dragon) and some people (workmen repairing bridges). I stopped to chat with some workers to see where I was - four kilometres from a shop! They were impressed that I could detect some of them were speaking Mongolian, and I was impressed with their down-to-earth happy-go-lucky mentality. However, the urge to devour packs of wafer thin biscuits was insuppressible and so I started salivating like a Pavlovian puppy.

On Tracks & Trucks

Refreshed and replenished, I set off with extra energy. About 12k later my chain snapped. Of all things to go on a bike, the chain ought to be pretty low on the list, but hey, this is China. A quick inventory of my Chinese-bought products which have failed would read: tent, tent bag, panniers, shoes, computer, clock, camera, batteries, and tow-rope. This last one was used to secure things to my bike, and although the rope didn't snap (unlike the one my junior students used for tug-of-war in school), the clip at the end is malfunctioning, and could work itself loose. Such shoddiness could lead to deaths; imagine a car being towed through the alpine road that Charlie Croaker et al used to make their great escape from Italy. If you haven't seen original Italian Job, go watch it, as it is an absolute gem of a film. I would be interested to know people's theories as to how the heroes successfully escaped from the perilous coach-full-of-gold-hanging-off-mountain-in- unstable-equilibrium problem. Anyway, my point is that roads exist where a broken towrope equals death. So come on Chinese workforce; stop the lies, shoddiness and scams and give us some quality. Having said this, I am rather fond of the make-do-and-mend attitude; I was certain that the next repairman would be able to rig up a solution based on banging existing parts into shape, whereas back home they'd insist that you bought new components.

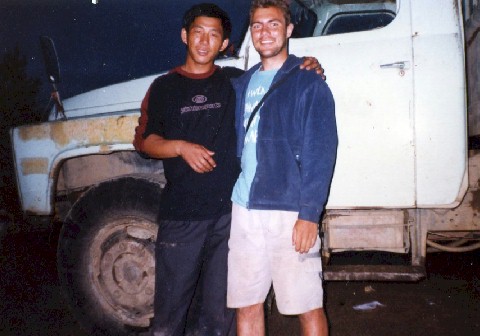

The net result was that I found myself hiking instead of biking. After 10 km (ain't km markers brilliant? the Chinese are great at this, just to show I give credit where credit's due) of dragging my bike up hills and holding on for white-knuckle rides down them, I heard a motor, and hailed it. It turned out to be two truckies going in the same direction as me, and they were not averse to me chucking my bike in the back, hopping in the front, and enjoying the ride with them. And boy, what a ride it was. Just like seeing the grasslands around Manzhouli gave me a whole different perspective of the town, seeing the track from a truck's cab gave me a whole new perspective of the road, and the beasts that I shared it with.

The drivers formed a good tag team; one was the all-smiles, talkative type and the other was the more serious, practical one, whose style I liked much more. Both their qualities came in useful later though, as we had an interesting truck-submerged-in-river situation somewhere between Twenty-Three Station and Twenty-Two Station. Before I had seen the density of the forests, I had thought that this string of stations might manifest itself as a series of military installations. This theory made sense, as they were aligned on the road nearest to the Black Dragon border river. Or maybe this road was the old border; I know Russia ceded some land to China at some stage. Pre-trip I had searched for information but had drawn blanks everywhere.

One of my truckies was a top bloke and a damn good driver over tough terrain; the other was a bit of a chump. This being the rainy season, there were plenty of "streams" to ford, though many were raging torrents and several car-lengths wide. Pragmatist - as I christened the favoured driver - had a great eye for which streams you could attack at 50kph and come through unscathed and which you needed to essentially stop before crossing. Idiot Boy revealed that he was a great theoretical driver, telling my pragmatic friend when to employ second gear (Chinese drivers stay in fourth unless the engine is about to die) and generally offering hints and tips. When the changeover happened, Idiot Boy proceeded to steer as late and as sharply as possible at every corner, lurching and bouncing along, and generally giving his already beaten-up truck a real battering. He seemed to employ the stream-fording tactics seemingly at random as about 50% of the time he was wrong, whereas Pragmatist had about a 90% success rate.

Stuck in the Mud

We approached one waterway that was deep, wide and had a truck in the middle of it whose owner had stopped to wash it, thus hogging the good rocks and forcing my driver to either wait or take a diversion. He steered around the obstruction only to find himself plunging into a less-visible one: quicksand. Quicksand ain't so quick; you generally reach an equilibrium in it without sinking further unless you struggle. The scientifically minded might be interested to note it is caused by masses of alluvial particles (ie sand or rocks) supported by circulating water as opposed to each other. Put anything in it, and you upset the equilibrium. However, its density is greater than most things, so you ain't gunna go all the way down, even if you are a big truck. You're just gunna find yourself a lower equilibrium point as the system re-stabalises. The more you struggle, the lower you go. So nothing perilous at all; just a "what now?" situation.

Well, road-hogging vehicle-washing truckie's mean machine was a real workhorse: it came complete with a gigantic crane and a heavy-duty winch. I never did establish if he was here for the sole purpose of winching people through or not, but it would be ironic if he, the problem solver, had been the cause of our little dilemma. I liked him too much to put forward the cynical suggestion that this was a case-in-point of the Chinese method of business-creation though.

All's well that ends well

Anyway, it is at times like this when true characters shine through. Firstly came the deliberating. Idiot Boy had run out of advice and it was Pragmatist who enlisted the services of Winch Boy and debated strategy. By the time an agreement had been reached, the entire police presence of Twenty-Three had come to "help" (read "observe, offer their ridiculous theories, accuse me of being soviet and demand to see my papers, and generally just be fat and useless"). Winch Boy was a strong, friendly, amiable man. Although his winch knowledge was unquestionably the best of the bunch, he was here for winching, not for theorising, He was here to serve and wasn't about to risk his neck and offer a solution that ended in disaster. Instead, he would take on the best of the Pragmatist's suggestions, refuting any that were not good, and steering my driver towards his own personal recommendation. I liked this attitude a lot. It was Pragmatist that got down-and-dirty and dug out a wheel or two and attached the winch, whilst Idiot Boy buttered up the local police in case oil or suchlike needed replacing or in case we were all going to have to abandon ship and spend the night in Twenty-Three.

After much deliberation, winching solution number one failed spectacularly. I guess winchers and winchees ought to arrange a code of communication pre-winching, like one toot for "go" and two for "stop", as "stop" they should have done before our truck failed to make it up the bank, almost overturned, and imbedded itself much deeper in the river. Winch Boy took a lot of convincing from Pragmatist that a second effort from the other side should be undertaken. Pragmatist looked pretty concerned about the whole thing, whereas Idiot Boy was having a ball. I guess, in his eyes, everything is all fate, and things just happen to him. On the other hand, Pragmatist had got us stuck in the mud, and was determined to get us out. He wasn't prepared to lose truck + next assignment + job (?) right here, right now.

At this stage I wanted to remove my bike from the truck. It wasn't that I didn't trust them; it was just that if that thing tipped, all my belongings save the clothes on my back and the valuables in my pockets would be ruined. I felt like poor Passepartout - the unwitting round-the-world travelling companion of Phileas Phogg in Jules Verne's classic Around the World in 80 Days. In the American leg of their audacious voyage, their train driver had stopped rather than attempting to cross a precarious railway bridge further down the track. Someone had the wild idea of attacking it full steam ahead, leaving it to collapse in their wake. It wasn't that PP's companion disagreed with the idea; it was just that he though the passengers should disembark before the attempt. Despite his logic, he was branded a faithless coward. So too with me: the fattest policemen didn't allow me to remove my bike on the basis that the Chinese are very clever and will sort this little thing out. I feel I don't need to pen my thoughts at this point.

Winch Boy followed orders for winching effort number two, but either didn't have enough horsepower or didn't use enough to get us out, so he abandoned his effort and winched a couple of smaller cars through instead adding evidence to the theory that this was indeed his role. Then everyone deliberated for ages. I sat in the truck to avoid idiots and mosquitoes and to generally muse about the situation. The delay wasn't an issue for me - I'd already gained oodles of time by hitching a ride. When I looked over my shoulder the scene was deserted - they'd all cleared off. Even the police. I allowed myself a little sleep.

Maybe an hour later the three amigos reappeared with a bigger, badder truck, much to the hilarity of Idiot Boy. They had a bigger, badder entourage too: 'twould seem that winching was a spectator sport of significance in these parts and most of the residents of Twenty-Three had gathered to watch. Pragmatist oversaw the whole thing and got us out the stew in the end, but had to correct some awful steering errors by our unfavoured theoretical driver, and then had to repair the truck back at the village. He was mightily relieved when the engine started. Idiot Boy was in charge of offering cigarettes to the police and playing the try-to-force-gift-on-someone-who-will-try- every-trick- in-the-book-to-refuse game that is oh-so tiresome. But it's the type of thing Idiot Boy was highly skilled at, alongside regaling all and sundry with tales of how he'd seen tigers in the forest. Pragmatist preferred to listen to facts about England. All was well and good; we stopped for dinner at Twenty-Two and made it to Eighteen before midnight.

The following morning I left my bike with a repairman, demonstrating the multitude of faults. I essentially said: "I don't want cheap; I want good because I want ride bike to North Korea". This gave rise to some arched eyebrows. He looked over me and looked over my bike for a good two minutes before responding.

"Hao le, hao le,"” (OK, OK), said he.

I had never tried the strategy of over-bidding someone before, and it didn't seem as though many customers came his way without haggling. I prayed he'd be able to rig something up that could at least last until Huma, a big river town 150km downstream. Money was lasting better than expected and so I wasn't concerned if I overpaid Mr. Fix-it (who, for obvious reasons, I christened Jim).

The Gold Road

Whilst Jim was seeing to my bike, I wound up eating eggs and tomatoes with Jeff, a resident Eighteener. I asked him about the naming of the settlements in the area, but could not understand his answer. Hence I got him to jot down a (very) potted history of Eighteen Station which another friend translated into Chinglish via the internet. Here goes:

In Man Qing, the Queen Mother had a gold mine called the "Blusher Ditch," have built a post from Nenjiang to Mohe. Nenjiang is one station, it analogises with this here that the treasure of Mount Tanbao also called as a station or the 18 places and the gold road.

So there you have it, the numbers were not a string of border checkpoints at all. Amidst all this nothingness they reckon there's some gold. All in all, this explanation is as weird as the terrain and the folk that inhabit it.

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.