Break for the Border: Cycling the Sino-Siberian Boundary

"I should perhaps point out that almost my entire mission was illegal, as the majority of the border zone is off-limits to foreigners. I didn't have a passport, let alone a permit, as mine was sitting in the Mongolian embassy in Beijing. What I did have was the remarkable Tourist Atlas of Heilongjiang Province, a publication which conspired to mark tourist spots in the middle of nowhere."

After teaching English in China for a year, I got frustrated with the uninspiring cast of characters that I all-too-frequently had to play. These included:

- Panda (let’s all stare at the whiteboy)

- Idiot (just because he can’t speak Chinese doesn’t mean he doesn’t know how to use a kettle)

- Robot (he’s a teaching machine and is purely here for our benefit)

- King (let’s shower him with gifts and attention and give him everything he could ever want…except his freedom, which is the only thing he’ll end up really wanting)

- Fashion accessory (look at me…I have a foreign “friend”…I’m so cool)

I decided to take action in the form of a new guise: the Russian. Simply bringing my white face to the northeastern hinterlands made me fully qualified for the part. And then I was ready to play the little game of “let’s cycle along the Sino-Siberian border until the police, army and village idiots take exception to my presence”. So without further ado I’ll take you to no-man’s-land.

Inner Mongolia, here I come!

(Thanks, Ivy)

Found it!

The journey began in the Inner Mongolian grasslands. I camped as close as I dared to the China-Russia-Mongolia tripoint, keeping out of site of the military compound whose name translates as “New 100 Road Capture”. How very inviting! Day one took me through real Mongolian territory; never-ending vistas of undulating land covered with stubbly brown grass and dotted with sheep, herdsmen on horseback and their beautiful sheepskin tents, known as yurt. Everything about this place was big: the sky, the wind and the enormous raindrops. Navigation was hit-and-miss as roads and reference points were non-existent in these parts.

Camping near the intimidatingly named New 100 road capture.

Russia is about 3km in front of me and Mongolia about 8km to my left.

Amidst the nothingness I saw something that I’d been wondering about for months. It all started with a line on a map. Not just any line, but a crenulated one running for more than a thousand kilometres in eastern Mongolia before crossing into China and slicing through the Russian town of Zabaikalsk. What’s more, the graphic was the same as that which marked the Great Wall. Intrigued, I began to search for information but drew blanks for ages. No other maps marked this wall. My mapmakers couldn’t have created a fictitious wall, could they? But in other respects their map was the best of the bunch and I doubted it was their mistake. So why had their cartographic competitors ignored such a large feature? The answer was that the wall had been eroded to such an extent as to be considered by many to be long lost. Whilst the Great Wall was built from stone, the Mongolian version was an earthy embankment. Which was exactly what had caught my eye. Maybe three feet high and four feet wide, it extended beyond the horizon in both directions and was undoubtedly man-made. I must have ridden over it the day before without noticing. Oops! I managed to take a picture of a Mongolian herdsman by this site but may be lacking a photo of self, as said Mongol attempted to operate the camera whilst looking through the lens rather than the view-finder. Ironically his name sounded like Fuji.

My Type of Town

They say only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun. They were both at large on this day, and quite unaccustomed to having competition in the insanity stakes. My “sain bain uu”s (hellos) went largely ignored; the first words many Mongolian herdsmen exchange are “nokhoi khorio!” – literally “hold your dogs!”. This hints at the savageness of these beasts, and consequently I was chased by evil canines for kilometres at a time. As for the Englishman, the few souls I saw in these parts thought I was nuts to use a bike out here. Gestural conversations established the superiority of the horse, which was undoubtedly a better person-propelling device over such terrain, but was one that I lacked the ability to ride, and one that wasn’t part of my mission.

I was as dehydrated as the arid land I had ridden over and my T-shirt was as salty as the dried out lake beds I had passed by the time I reached civilisation. And for me, Manzhouli represents the height of civilisation. Last stop before Siberia, this railway town is the perfect place for people-watching. Its population is remarkably free of the afflictions of averageness and normalcy that are evident in so many of us. Deviants encountered in this place include Marx, a drunk Russian boxer who couldn’t understand that I couldn’t understand Russian and had a penchant for picking fights with taxi drivers (I refer to him not me), Prince Martyr Saul, who may or may not have been a Korean pastor wandering around the Inner Mongolian grasslands in search of his dead grandmother, and Suzanna, the unforgettable girl of the sky whose family owned seven yurt and seven horses in the steppe. I roomed with two Kyrgyz companions whose collection of empty vodka bottles, cigarette butts and cartons of taken-away Chinese dumplings was even larger than the cluster of consonants in the name of their homeland. Ostensibly they were businessmen. On the outskirts of the town real Mongolians were serving real Mongolian fare: mutton, lamb and sheep. Much fun was had by all, and I vow to return one day. ‘Twould be the perfect place to learn a language or three, what with the mingling of Chinese, Russians and Mongolians.

In contrast to the cleanliness and laissez-faire entrepreneurial spirit of Manzhouli, the next town was a blue-collar industrial eyesore. However, dirt equalled pay-dirt – it was a mining settlement. They still use steam trains to haul coal out of huge open cast pits, and I got to ride on one for a while. I also got imbibed with alcohol and think some yokels slashed my tyres in an effort to keep me away from the border, but I’m rather hazy about that little episode. I had a long walk back to a bike shop to contemplate it all, however!

I left the historic trains behind, but hadn’t finished with historical railways. I paused as I crossed the Trans-Manchurian line and, seeing barren land in all directions, both Moscow and Beijing seemed a long way away. Probably because they were. Once upon a time the Japanese had been in control of this stretch of the track and, indeed, much of Manchuria. They were civilised enough to build some underground tunnels which provided much-needed respite from the heat of the desert. However, what they did down there was far from civilised. They conducted medical experiments on the Chinese that make Nazi gas chambers look like veritable Jacuzzis, and Hitler like Florence Nightingale.

Exchanging the horrors for the hills, my journey from Hailaer to E’erguna (Argun if you’re Russian or want something easier to pronounce) brought a change in scenery. There was a gradual transition from the brown sands and stubbly grasses of the steppe to rolling green hills that looked surprisingly Scottish. There were plenty of localised storms, some of which I could out-run on my bike. At one time I counted four on my right and three on my left and when they and I converged, I ducked for cover in a conveniently located roadside restaurant. There I encountered a grey-eyed Mongolian, possibly of Russian stock. Back on the track there were swarms of beekeepers lining the road. I never imagined the Mongolians to be a honey-loving people, but the world is full of surprises.

Land of the Sheep

Argun ‘City’ is just beginning to open up, thanks to the Argun River Bridge. This provides a link with Russia, and represents the only such structure joining the two nations despite the fact that more than 3,000km of their shared boundary is marked by waterways. The bridge opened in 2001, is located in the Inner Mongolian hinterlands and no-one had heard anything about it, even the locals in the town in which it served. Did they not wonder how the “big noses” got here? The mystery made it a must on my border tour. On my way to explore it I was overtaken by a few moon buggies – well, that’s how I think of a particular type of Soviet jeep that looks like something a 70s scientist would come up with if given the task of designing lunar transportation. The valley was immensely wide as the river lazily meandered along its course. It supported low-growing, water-loving trees, which gave the impression of an impossibly wide green river from a distance. The “insect incentive” kept me pedalling, as a momentary break would cause me to be savaged by a swarm of aerial enemies.

I stopped for dinner in a small village and merely asked for lamb, knowing that this was the land of the sheep. Surely they would be able to concoct a wonderful dish for me. They took me into the kitchen to choose my pieces of meat, cooked it, and, err, served it straight up. Bones and meat on the plate, a bit of sauce at the side, a soup made of the juices, and a little penknife to carve off hunks. It wasn’t what I expected, but was nice all the same. I probably lingered in this village a little too long, but it was necessary to buy water from a shop and re-tie my bags to my bike. As I was doing this, some policemen came, and I felt a little annoyed, because up until then I had been able to get away with being a “situational Soviet”. What I mean by this is that if anyone wanted to talk to me then I had the option of either being the real me, able to converse a little in Chinese, or I could just use my literal and metaphorical “dimmer switch” and reduce my perceived comprehension to zero, just like my Russian cousins.

Anyway, when the police came, not only would I have to be English as per my ID, but I would also run the risk of getting sent back to Argun ‘City’, thus negating 50km of up and down cycling in the Inner Mongolian heat. Which is exactly what happened. Actually, the police were friendly and very interested in the parts of my journey that I decided to tell them about and were genuinely sorry to have to put a stop to it. They wouldn’t “sell” me a “permit” though. However, they pointed out other places worth going to and organised transport back to Argun. Well, I pretty much decided I wasn’t going to cycle back for psychological reasons. Other than my legs, my main source of power on this journey was a trailblazing spirit; the curiosity as to what lay over the next hill and where you’d get to if you turned down the most unlikely road into the hinterlands. Ignorance is indeed bliss and one can blindly set off to do things that one wouldn’t necessarily be so game for with prior knowledge. Like cycle on muddy mountain roads in the midst of the rainy season, which is what I did for the next week or so.

Braking for the Border

I left the grassy hills behind and entered a huge pine forest, home of the reindeer-herding Ewenke people. These are one of a handful of indigenous groups that inhabit both sides of the border. I didn’t see any of these Chinese Laplanders, but did see some landslides and several trees being swept down the swollen rivers. I was on the road to the “Arctic Village”, China’s northernmost settlement. I’d been there before in the winter when it was -40. My nose froze and I ate un-refrigerated ice-cream bought in the streets for comedy value. Mosquitoes were more of a danger than frostbite this time round, and local lore has it that they have caused the death of reindeer by entering nostrils in such numbers that the antlered beasts can no longer breathe.

Given that the Argun was a tributary of the Black Dragon and that I’d climbed a lot during the past few days, I knew I’d be going down, down, down. Indeed, four days’ worth of climbing was repaid in the final fifteen kilometres resulting in an awesome unbroken descent. Well, my motion was unbroken, but my brakes were very broken! I had no way of stopping myself as I gathered speed and hurtled round bends. I used my feet and slalomed down the road in an effort to keep my speed in check and prayed there were no bulldozers lurking around blind bends. There weren’t, but there were several streams to ford and I got some serious air-time as I hit one at an incalculable rate.

I saw the other side of the valley and knew I must be homing in on the mighty Black Dragon, the eighth longest river in the world and my companion for the next eighteen hundred kilometres or so. As I was straining to see the water, I noticed that my road would take a sharp turn to the left in a second. Too sharp for me, but fortunately a track continued straight on. Unfortunately it was the entrance to a military compound and had armed guards either side. Damn! I got through inches of shoe leather and skidded to a halt about ten metres from the soldiers. They were of the beefeater-esque mustn’t-move-a-muscle training and were stationed to face each other, their steely gazes forming a laser beam designed to intercept any miscreants daring to break their line of sight. On this occasion their training failed them and they turned to see a “foreign devil” on a bike smile and disappear pretty quickly. I hope they were severely reprimanded for their breach of discipline!

On Tracks and Trucks

How on earth was I to get out of this bottomless pit? I didn’t fancy doing the descent in reverse, so I posited the existence of a road alongside the river. Amazingly, such a strategy worked for 10km or so until I hit a dead end surrounded by impenetrably dense forest. So I backtracked and theorised a southbound road for myself, and contemplated whether I could also dream myself up a full English breakfast, a semi-accurate map, or indeed a rain-free day. Alas, my supernatural powers seemed limited to road creation, which I really ought to mention to the Highways Agency next time I need a job.

On my track I was passed by a couple of trucks which were serving a quarry of sorts, where men chipped the rocks by hand. Well, the hands wielded axes, but still, it looked pretty primitive. After hours of nothingness, a lone betractored yokel confirmed that this unlikely route did indeed link with my road east. At the connection was an absolute ghost town. There were maybe 50 houses, all derelict and littered with broken glass and wood chippings. This place was eerie. I was going to stop and take photos except it transpired that some people actually lived here, and had the type of body language that said “move on else I will fetch my rifle and send you to kingdom come”, so move on I did, passing under a barrier and onto my road, marked here by “688”. That’s a lot of kilometres to do on a muddy forest track, wherever the “zero point” is. During this time I thought a little about tigers, and whether or not they could climb trees, but considered that statistics was a far better defence than tree-climbing. Two days before I left the UK I had caught a documentary on the Siberian tiger, which replayed a single killing of a sheep about 18 times, suggesting they were kind of low on footage, which in turn suggested that human-tiger interactions were something of a rarity. Indeed, it is estimated that as few as 20 of the beasts are wild in China at any one time, the rest opting to terrorise the North Koreans and Russians. So “Oi! Big cat! Go eat Bell’s theorem, not me!”

Time progressed in a forwards manner, as it is wont to do. I didn’t. My chain had snapped. Of all things to go on a bike, the chain ought to be pretty low on the list, but hey, this is China. A quick inventory of my Chinese-bought products which had failed would read: tent, tent bag, panniers, shoes, computer, clock, camera, batteries, tow-rope. This last one was used to secure things to my bike, and although the rope didn’t snap (unlike the one my kids used for tug-of-war in school), the clip at the end malfunctioned. So I found myself hiking instead of biking. After several hours I heard a motor, and hailed it. It turned out to be two truckies going in the same direction as me, and they were not averse to me chucking my bike in the back, hopping in the front, and enjoying the ride with them. And boy, what a ride it was. Just like seeing the grasslands around Manzhouli had opened my eyes to the Mongolian angle of the town, seeing the track from a truck’s cab gave me a whole new perspective of the road and the beasts that I shared it with.

We had an interesting truck-submerged-in-river situation somewhere between the villages named “twenty three station” and “twenty two station”. It being the rainy season, there were plenty of streams to ford, and this one was deep, wide and had a truck in the middle whose owner had stopped to wash it, thus hogging the good rocks and forcing my driver to either wait or take a little diversion through quicksand of all things. Quicksand ain’t so quick, and the scientifically minded might be interested to note it is caused by masses of alluvial particles supported by circulating water as opposed to each other. Put anything in it, and you upset the equilibrium. However, its density is greater than most things, so you’re not going to sink all the way down, even if you’re a big truck. You’re just going to find yourself a lower equilibrium point as the system re-stabilises. The more you struggle, the lower you’ll go. Nothing perilous; just a “what now?” situation. To cut a long story short, we made it out after several false starts, had dinner at “22” and made it to “18” before midnight, where I found a room to stay and got my bike fixed on the morrow.

Baldies, Fatties and Crazies

On the road to Heihe I was temporarily put out of action by baijiu, a lethal Chinese spirit distilled from sweet corn. This beverage was proving to be more effective at stopping me than the combined efforts of the police and army. The next a.m. I was treated to a morning mist, and decided I much prefer this spelling than my “morning missed” through the after-effects of alcohol! The mist was breathtakingly beautiful and added an artistic touch to the giant cobwebs that hung across the forested road.

From the crest of a hill I sighted a red-and-white striped Russian chimney before I could see anything on the Chinese side and expressed my gratitude to communism in general and what it had done to my road surface in particular. You see, I was 20km from Heihe and found myself on concrete. One of my lasting memories of winter in the northeast was standing under cranes the size of skyscrapers and watching Siberian loggers drive across the frozen Black Dragon River at this prosperous port. Add in the fact that it was -30 and that I was under the shadows of a decaying concrete factory and that during a less friendly period between the two socialist states the Chinese had used megaphones to continually broadcast propaganda to the Russians, this scene had the nasty edge that I have always associated with communism. So too did Manzhouli in mid-winter. Seeing hundreds of wagons full of frozen logs being shunted around at night and in the middle of nowhere is kind of eerie. In fact, the whole logging industry has my full attention. On one side of the border you have an extremely sparsely populated nation which holds about 25% of the world’s forests, and on the other side you have the most populous nation on the planet without much in the way of trees (relatively speaking of course – I cycled through a primeval forest bigger than England out there!). When you factor in that Russia’s economy is faltering and that the Chinese mindset is all about growth, the inevitable result is a vast southbound exodus of Siberian logs to satisfy the seemingly insatiable Chinese appetite for burning, building, bureaucracy (which creates the need for a few billion documents) and transferring chicken feet, sheep’s eyes and stodgy rice from bowl to mouth (I refer of course to the multiple million pairs of disposable choppers used every day). Much of the trade is unregulated and illegal, and the transnational truckers contribute the bulk of the border-crossers at many of the ports.

But I digress. Deviation was the name of the game at Heihe too; I decided to take a break from the border and head for the volcanic formations of Wudalianchi, which translates as “Five large connected lakes”. The bodies of water were enclosed by fourteen extinct volcanic cones. The area contained bizarre rock formations, springs, caves, ancient lava fields and crater lakes and the majority of people that came here could be divided into two distinct groups: the baldies and the fatties. The former being leukaemia patients who came for the healing waters and the latter being obese Russian tourists. Riding off the tourist circuit I came across many run-down sanatoriums and hospitals, and heard screams from one. (Acupuncture?) Later I encountered an individual foaming at the mouth and nose and talking to the invisible man in front of her. Or herself. I guess I’ll never know which, but I knew that the time had come to leave this weirdness behind and get back to the border.

The Crater Atop Black Dragon Mountain

Back in Heihe I stocked up on two forms of Russian chocolate, the first being the timeless Mars bar in Cyrillic script and the second being a soft chocolate infinitely superior to the shockingly poor Chinese efforts. I took a stroll around the town at night, and somewhere in the shadows of the “communist-grey” apartment blocks, I felt a hand on my waist. ‘Damn, a robber, possibly with a knife…why the hell do I have so many valuables together?’ I spun around to assess the situation and realised that my “attacker” was actually a drunk homosexual under the impression that, as a white man, I too was that way inclined. I thought at the time his nose was lucky that I wasn’t a Russian truckie, but later experience taught me that maybe he was unlucky.

More Ports of Call

Further downstream I hit the town of Xunke the day before a festival celebrating the culture of the indigenous Oroqen people. I managed to wangle free tickets for the performance and witnessed colourful dancing, soulful singing and amazing acrobatics. From their style I assumed these folk were gatherers rather than hunters, and later forays to the forests confirmed this as I saw them collecting wild mushrooms in huge baskets slung over their backs. I realised just how lucky I had been to get tickets when I saw the size of the crowds that had gathered for the free outdoor encore, held at No. 2 Middle School. There was a beautiful firework display and much merriment throughout the night. When I hit the sack I wasn’t too amused to be kept awake by room-mates who were constantly questioning me. Their status as prime source of annoyance was superseded by some boys in green; the army had come and were demanding me to recount my life history. It was gone midnight. I answered their questions, showed them my ID and thought this would establish my legality and cause them to disappear (only I mentally phrased it a lot less politely). However, these kids were convinced I was their new foreign friend. It took hours to get rid of them. I had cycled 140km and was quite drunk – I didn’t need this!

The next day I realised why I had caused such a stir. The town does indeed have Russians shoppers who come across on a small passenger boat. They are all day-trippers and come to buy their 50kg worth of tack before leaving in the evening. This means the town has the bizarre concept of Russian and non-Russian days. I suppose Heihe must have Russian and non-Russian seasons, as the freezing of autumn and thawing of spring are amenable neither to the boats of summer nor to the vehicles which drive over the ice in winter. How odd! The next port seemed to run on this principle too, but I didn’t stay long enough to see a Russian day, and no-one knew when the next boat was coming. Outside the town I walked for miles to reach a stone saying “Fossil Site Number One”. I suppose the lack of an entrance fee to the dinosaur park was a giveaway that there wasn’t anything here any more, but I did see beautiful Russian dachas on the other bank and I made friends with a Chinese salesman peddling soviet artefacts.

Russians on a Chinese Island

The ports were coming thicker and faster now, and at the next one I met someone very interesting. She was a middle-aged Chinese woman who continually cracked guazi shells (a type of small nut) with her teeth, and offered me free baozi (steamed bread with meat filling). In fact, there was nothing remarkable about her except her job – she was the first pimp I had the pleasure of meeting. Two Russian girls worked for her on a Chinese island in the border river. The four of us attacked a mound of guazi for a while until the girls disappeared for some business. I slipped away so as to get my pleasure in another form – more ???? was to be had at this tiny port. I cannot understand why this exquisite piece of confectionary is imported at a couple of the smaller ports but not at the major ones. Hence I propose to fill the void, get the Chinese addicted to Mars, and make a tidy profit in the process. Seriously, the China-Russia border is thought to be one of the most under-exploited boundaries, kilometre for kilometre, in terms of trade potential. This appears to be largely due to mutual mistrust, although bureaucracy and lack of infrastructure don’t help matters.

After a few more brushes with those shady officials collectively known as the authorities, I arrived at Tongjiang, where I did my duty as a yellowish-haired fellow and posed for photos looking out over Russia. And then I made it to the port of Fuyuan which is further east than “Lord of the East” (Vladivostok). I spied the disputed islands that would be the easternmost point in China, were it not for Russian claims. Pravda, the Russian news service, recently reported the burning of a historical Russian map which supported the Chinese claim. Things aren’t particularly heated now, and the islands have become stepping-stones for caviar smugglers, of all things. I managed to miss the easternmost village due to a miscalculation (d’oh), and had 80km of cycling negated thanks to the powers that be. They did give me yellow tomatoes though, and one can’t argue with the bearers of free foodstuffs.

I headed south alongside the Wusuli/Ussuri River, site of unpleasant border skirmishes in the late ’60s. The only noteworthy port was Raohe, home of Danya. She’s Chinese but makes her living selling cheap goods to Russian truckies, such as Sasha, Sasha, Sasha and Valerie. Day in, day out she flirts with the drivers and keeps track of numerous transactions in yuan and roubles, 60 of which she gave to me for free. I’m guessing that in the 11 years since the opening of the border, she’d dealt almost exclusively with Russians, as her Chinese was coloured with a Russian accent. Bizarre. I had to take evasive action from her shop when I found myself fending off homosexual advances from Sasha III. Maybe he should operate on the Blagoveshchensk-Heihe run; I could put him in touch with someone who’d be keen to receive him!

An Unusual ‘Passport’

I was now riding a gearless beast, the same machine that serves millions of Chinese peasants. (I had traded my battered “mountain” bike for a pack of cookies and a couple of bottles of water, which was a fair reflection of its value after I’d tested the malleability of the frame, mangled the chain and sprinkled several vital components among the trees.) I loved my new bike; it was faithful, dependable and strong as an ox. And it was taking me down roads that weren’t marked on maps and through another series of villages that had numbers rather than names. I saw the most ghostly border crossing of the lot, with only a duck-farmer’s lodge and a few abandoned cabins before a barrier and border complex. Odd.

The coldness had been creeping in night-by-night, and I vowed this would be the last time I’d shiver under canvas without a sleeping bag. Bright and early I set my compass and headed south, only to find my track terminated in some fields right by the border river. Nothing for it but to turn around. For once I was glad to see the police as they gave me a lift in their 4WD to the nearest station, which was miles away but in the right general direction. The usual drill of Qs and As ensued and their initial suspicions that I had or was going to jump the border soon subsided. They told me about a German who they’d encountered in the past. I gathered he was hiking with a huge backpack and couldn’t speak any Chinese. It must have been one hell of a walk from where he started, as this was miles from anywhere. I guess they think all foreigners are subnormal now. They pointed me towards the lake and I was off again.

Xingkai Hu/Lake Khanka was immense and stretched beyond the southern horizon into Russia. Yep, Russia was south of China at this point. Whilst the surface area was huge, the depth was tiny, reaching a maximum (minimum?) of four metres. Actually, there were two lakes; the big one and the little one, with a causeway between the two. The little one was calm, serene and peaceful with fishermen idling in their boats between the reeds, lilies and grasses. The big one had 40km of continuous beach lapped by gentle waves. Oh, and a JCB drove through it about 50m from the shore. Other than that, I had it all to myself. There was a tiny fishing village in the middle of the causeway which almost became the second visually-appealing Chinese settlement I’d seen. Cheap red-bricked houses and dusty streets strewn with detritus are the norm whereas I love houses built from local stone. Manzhouli is the only exception; it has beautiful log cabins with filigree windows in true Russian style. They even go easy on the apartment blocks. Back to the lake, the only bad thing was the road, which was too sandy for cycling for the most part (hence the alternative route by the digger). However, skinny-dipping more than compensated for this, and the coldness didn’t detract from my refreshment after X days without washing. There was a border checkpoint on the western shore where Chinese hawkers scrambled to make some final sales to busloads of returning Russians. Then I had to think about my route for the next stretch.

And to think I had it all to myself!

I had my reasons for wanting to avoid the city of Jixi. I could see from the map it had too many qu (districts) and was therefore likely to be an immense urban conurbation. So I decided to take an alternative route through the countryside on minor roads skirting the border. A village policeman picked me off in the mountains and detained me. He phoned through for the border police, who drove me to the city police, who conducted an interrogation with an English teacher there to translate. The best question was “tell me your life history from middle school onwards”. They kept me beyond midnight, confiscated some photographic film and made me confess to the error of my ways.

I should perhaps point out that almost my entire mission was illegal, as the majority of the border zone is off-limits to foreigners. I didn’t have a passport, let alone a permit, as mine was sitting in the Mongolian embassy in Beijing. What I did have was the remarkable Tourist Atlas of Heilongjiang Province, a publication which conspired to mark tourist spots in the middle of nowhere. An endless stretch of taiga was designated as a Forest Park, for example, and a particular portion of the steppe was the E’erguna Banner Scenic Spot. Thus I essentially had a series of maps with more blobs than a pepperoni pizza (or its teenage delivery boy, if I were being particularly harsh). Whenever my movements were questioned by the police, I could whip out the atlas and do a little dot-to-dot exercise, and I would always be connecting legitimate tourist spots. I enjoyed this strategy. Thus the book was essentially my passport, and my mallet was my toolkit. Being clueless in even basic repairs, I would rely on the ever-present bikemen to keep my machine going. The problem was that minor faults would invariably be patched up to the extent that the squeaking and grating would ease for a hundred kilometres or so, only to reappear. As it was too difficult to convince the bikemen to install new parts (going thoroughly against their make-do-and-mend philosophy), my solution was to make a minor fault into a major one by hitting it with a mallet. Again, effective and enjoyable!

And so I saw Jixi after all. It didn’t disappoint; there were smokes in various shades of grey, brown and yellow (they must have “industrial snow” in the winter), a cooling tower in the city centre and open-cast coal mines and slag heaps in the suburbs. There was even a shop bearing the sign “PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA: REGISTERED PROSTHETIST” which had legs and the like in the window. The presence of a market for artificial limbs suggests industrial accidents are rather more common and rather more nasty than I would care to imagine. Traffic accidents were more of a concern for me as I got sucked into a fast-moving eight-lane affair which came to a five-way junction, minus any signals or, it would seem, rules. I took refuge in some roadside refuse (the cars tended to avoid the piles of bricks, but that was about all), set my compass to choose my route, and tried not to breathe until I cleared the suburbs.

Refreshingly Russian

Lonely Planet notes that while most nationalities understand that a train compartment is the property of a company and they are merely temporary residents, the Russians take over the entire space. And they sure have the run of the border-towns too. Nowhere is this more evident than Suifenhe, gateway to Vladivostok. Everyone who’s anyone in the town speaks Russian. There are even Russian-only nightclubs where middle-aged peroxide blondes strut their stuff to Russian rap whilst scientifically researching whether the lungs or liver will be the first to crack when tested to destruction. On arrival at this frontier-town I had borsch and steak with a couple of Chinese architects. They knocked back their ale, and were trying their best to set me up with Masha, a waitress. In other parts of China these girls are known as fuwuyuan, which equates to “maid” or “waitress” according to a dictionary. However, the lack of respect people give them as they holler “FUWUYUAN!” makes “slave” a more accurate translation. The Russian name-badges for the Chinese waitresses were a nice touch and made for better customer-client relationships, which my comrades were keen to advance even further. Masha was quite cute, but Sonya was infinitely more desirable! The shop assistants had Russian names too, and their stores bothered stocking large sizes for the oversized lao maozi (Hairy Ones) that they served. How very refreshing.

In the morning I got up and intended to just walk around and blend in. I saw a procession of brightly dressed young people wielding flags, and thought it was fair game to tag along waving a T-shirt with a view to deducing their purpose and endpoint. It turned out that they were college students and it was their sports day, and nearly all of them learnt Russian rather than English. And they had foreign teachers, as I discovered when I got to the sports ground. Two were middle-aged and exhibiting non-natural hair colours and nicotine addictions whilst Yulia was fresh out of uni and refreshingly clear of such symptoms. And she spoke English. She’d spent a month studying Chinese in Jixi of all places (the ugly city I had tried in vain to avoid) and was now embarking on a ten-month teaching challenge that I could relate to. I stayed a week, semi-voluntarily taught English and, when the time came to say our dosvidaniyas (goodbyes), I was sorry to have to leave.

Food for Thought

My favourite road sign of the entire journey came on the stretch from Suifenhe to Dongning. It informed me that the next 14.5km would be of a gradient of 5.1%. Downwards! ‘Twas some payback for all those signs back in the mud roads that taunted me by informing me of an incline when I had already dragged my bike uphill for a kilometre or so. The port was located in a village teeming with ethnic Koreans and I stayed with one such family in their restaurant. They served me dog soup for breakfast – pretty tasty stuff. I was to sample foreign fare again in the early afternoon, thanks to the occupants of a car I saw going the other way. After spotting me, they stopped and got out.

“Ni hao,” said I, using the Chinese greeting. But then I realised that the passenger was a fellow foreign devil.

“Zdradsvuitye,” I tried, mimicking the Chinese mimicry of the Russians. She said something that I didn’t catch as her serious-looking husband emerged, so I tried: “Angleeskee. Nye russkie.” To which she responded, “I am German. Where are you from?”

What the hell was a middle-aged German couple doing on a dirt track in the Chinese hinterlands? They didn’t look like backpackers and they weren’t. Werner Schlusser was an engineer working at the VW factory down in Changchun, a city which I had described in my winter report as “an industrial monstrosity that served as a transit point only”. His wife had come over for holiday and they were driving northeastern China. They’d been to Jilin (“taxi driver informed us that meteorite museum was closed and that there was nothing of interest in city”) and their next destination was Jixi (home of the cooling tower and prosthetist)! Inexplicable decision making on his part, but we allow for bad judgment from those who not only come bearing beer, but also provide authentic German pumpernickel and leberwurst. What on earth would I be eating for dinner, I wondered. Or would I be eaten for dinner? This last thought emanated from the fact that my road, brilliantly described by the Germans as a “katastroph“, went through a Siberian tiger reserve. One of the English teachers at Suifenhe had told me the tale that a tiger had jumped 4m over a fence and killed a man last week. I didn’t believe him then and believed him even less now; there were no fences! And night was falling. I cautiously crossed the provincial boundary – what a welcome to Jilin!

Luckily there was a battalion of trucks stuck in the mud. The entire road was blocked and so these guys weren’t going anywhere till the morning. I spent seven hours shivering in one of the cabs – where’s baijiu when you need it…that stuff would have warmed me up. I made an early getaway and noticed the frost on the ground – this was the first sub-zero night of the journey and I was glad that I’d be finishing soon. After negotiating the tiger reserve without further incident, road signs were bilingual and all the locals were ethnically Korean. I was homing in on the (decidedly un) Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the end of my mission.

End of the Road

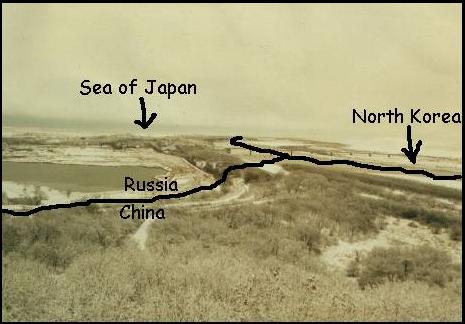

The last day brought a few firsts. First tunnel, first snake (road-killed though) and first crash (caused by the first first). In places the scenery became eerily reminiscent of that from day one; brown grass failing to cling to sand dunes. I was riding alongside the Tumen River and attempting to travel to the tip of a tiny finger of China wedged between Russia and North Korea. I didn’t rate my chances, especially after seeing the extent of the military presence in these parts. I passed a bilingual sign which said “UN World Peace Park 11km” and wondered how many people had benefited from the English display. There can’t be too many westerners that have made it to this neck of the woods, even though the Chinese designate the tripoint a tourist attraction. From the license plates of cars I gleaned it was enough to attract people from other provinces. At the end of the cul-de-sac was a small hill, complete with a military watchtower and a civilian observation plateau.

From the plateau one could see three countries at once and the bridge linking the other two. One could even see the Sea of Japan – from a landlocked province no less! Hmm, next time I should make use of this knowledge in the form of “sucker bets”. The method being as follows: I bet a Chinese man that I can see the sea from Jilin Province. If his geography is up to it, he will passionately argue that this can’t be done as Jilin has no coastline. Then it’s time to introduce the subject of renminbi (literally “people’s money” – the Chinese currency), produce the proof, and win myself some nice “redbacks” complete with Mao’s podgy face. Sure beats teaching!

So, that was that. I gave my battered bike to the bemused soldiers at this strange outpost and hitched a lift back with some schoolteachers who had brought a load of 11 year-olds here in the holidays (I dunno about you but at that age I spent my holiday time attempting to transfer the pebbles of Budleigh Salterton beach into la mer one-by-one). Anyway, having seen glimpses of Russia for more than 4,000km, I am deadly curious to know what life is like on the other side. And so I think I’ll pick up from where I left off. Well, on the other side of the bridge, in any case. Yes folks, I’m planning to cycle from North Korea to Norway; two countries that could barely be closer in an encyclopedia yet could hardly be further apart in terms of politics and lifestyle. Two countries separated by seven time zones yet bridged by a single nation. North Korea to Norway by bike. Trans Siberia sans train. Insanity. Call it what you will, it’s my next little game.